B. “SHARING THE BURDEN”: A NECESSITY FOR EUROPEANS

1. The historical role of the United States in Europe since the Second World War

Since 1945, Europe has been in a situation that has never occurred since the fall of the Roman Empire: it has largely lost its responsibility for defending itself. Several countries in Eastern Europe underwent Soviet domination from 1945 to the 1980s, which for half a century deprived them of the possibility of determining their own defence policy. In Western Europe, in the context of the Cold War, the European countries by and large placed themselves under US protection, in the framework of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) created by the Washington Treaty of 4 April 1949.

Only two countries have chosen to maintain an autonomous capacity to defend their vital interests by rapidly acquiring nuclear arms: the United Kingdom (which has had nuclear weapons since 1952) and France (which has had them since 1960).

Even today, the United States accounts for about two-thirds of NATO efforts. The situation now, however, is that faced with the growing challenge of China's hyper-power status, the United States has made clear to its European allies that it no longer intends to play such a substantial role in the defence of Europe. That is what the United States means by its regularly repeated demand for “burden-sharing.” By the time of the 2006 Riga Summit, the allies had agreed to raise their national spending to a minimum of 2% of GDP. It was in this context, that this prospect was confirmed at the 2014 NATO Summit held at Newport, by a specific commitment that the allies would make that figure the goal to be reached in 10 years. 29 ( * ) A second goal was that at least 20% of these defence budgets would be allocated to equipment purchases.

In fact, the end of the Cold War led the European States to believe that they would be able to “collect the dividends of peace” by continuously reducing their defence efforts.

The significant element of this new context is that two developments not directly related to one another have met and converged:

- On the one hand, the United States has found itself facing challenges on a global level of a kind not seen since the Second World War, and has felt the burden of its commitment to European defence more acutely;

- On the other hand, the European States have become increasingly aware of the threats they face, especially in the wake of Russia's annexation of Crimea. This was a symbolic shock, because it dramatically manifested Russia's will and ability to challenge internationally recognised borders, including those that it had itself recognised until then.

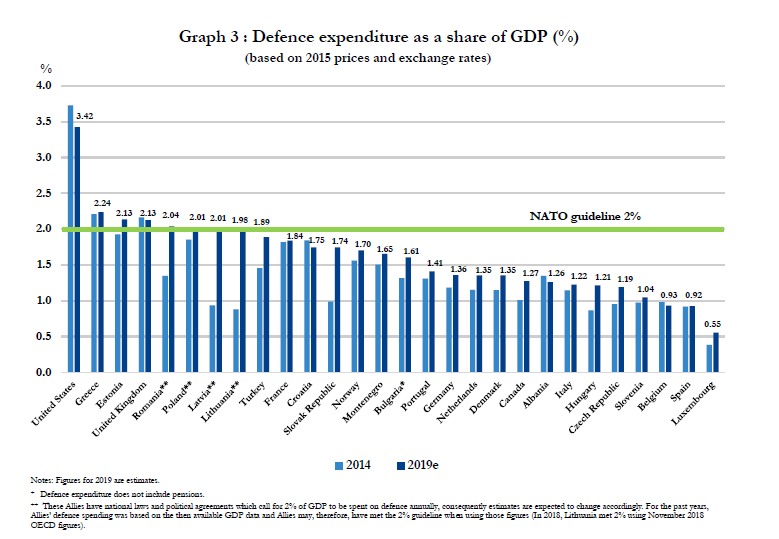

Source: NATO

The graph above shows the increase in the share of defence spending in GDP for most European countries between 2014 and 2019. Expenditures have increased for the fourth year in a row. However, for the time being, the majority of European NATO members still fall short of the 2% of GDP criterion. 30 ( * ) This is particularly the case in Germany, at 1.36%; Italy, at 1.22% and Spain, which is at 0.92% of GDP.

Here, American and European perspectives diverge. It is quite clear that for the United States there is no common measure between these two challenges. For the United States, China is a universal competitor, contesting American supremacy in all domains: first of all in the economic domain, then in the financial domain, and in the cultural, diplomatic and strategic domains as well. In this competition, the military dimension does not dominate, although it is present.

Russia has the opposite profile: it is a country with a weak economy, and a GDP between those of Spain and Italy - even though it is the largest country in the world and endowed with considerable natural resources. In addition to this, the Russian population is undergoing a net decline. Though Russia's interventionist and sometimes provocative policies pose a clear and immediate threat to European countries, and are of course more urgent for those closest to it, it does not pose a threat to US pre-eminence worldwide. These are the issues at stake in the organisation of the system for arms control in Europe, a matter that is of key importance for Europeans. In this light, the scheduled expiration of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty next August is extremely concerning. Significantly, the issue is the subject of very broad consensus in Europe.

This, then, is the deep root of the awakening of the European spirit of defence: our fundamental security and defence interests have diverged from those of the United States. But this divergence, of course, does not mean opposition.

Extremely strong ties unite the countries of Europe to the United States. These ties are multiple, and range across all the economic and social fields, but in general they may be considered as being of two fundamental types:

- First there are blood ties, forged in common military engagements against common enemies. While these ties are particularly old in the case of France, it can be said that they include all European nations, in respect of the liberation of Western Europe in 1944-1945. As we have lately been commemorating the 75 th anniversary of the Normandy landings, your rapporteurs here wish to take a moment to salute the memory of the thousands of American soldiers who gave their lives during the campaign in France. Their sacrifice cannot and will not ever be forgotten, and has forged an eternal bond between our two peoples.

- Then there are ties of a political nature. The United States is a democratic regime, based, in the same philosophical and ideological tradition as the European countries, on the belief that every individual has inalienable rights, and that the rights and duties of all members of society are defined and protected by the rule of law. This is an abiding, fundamental difference between the United States and other powers like China or Russia.

The use of the term “burden-sharing” in regard to European defence would thus seem appropriate. In substance, then, it is difficult to see what could lastingly justify Europe's continued under-sizing of its defence efforts.

2. Stabilisation does not yet mean rearmament

The analysis of quantified comparisons made by the Swedish Institute SIPRI helps put European defence efforts into perspective. A medium-term analysis of these comparisons (over a decade) shows some surprising results. Looking at the period between 2008 and 2017, SIPRI has identified four groups of countries: 31 ( * )

- Those whose defence budgets have substantially increased, by at least 30%: China, Turkey, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Australia;

- Those whose defence budgets have increased by between 10% and 30%: South Korea, Brazil and Canada;

- Those whose budgets have increased by less than 10%: Germany, France and Japan;

- And those whose defence budgets have fallen: Italy, the United Kingdom and, above all, the United States.

Particular attention should be given to the United States and the main European countries. Over this period, the defence budget of the United States decreased by 14%, and was down 22% from its peak in 2010, when increased efforts were being made in Afghanistan and Iraq. This relative decline cannot, however, conceal the massive size of the US military budget, which in 2017 came to $610 billion, 2.7 times that of China, the second-biggest military spender.

In that same year, 2017, all the European countries combined (including Russia, in keeping with SIPRI classifications) spent $342 billion, i.e., 56% of the US effort. Unsurprisingly, the largest defence budgets in the European Union correspond to the largest countries, in the following order: France (6 th in the world), United Kingdom (7 th ), Germany (9 th ) and Italy (12 th ).

As the SIPRI report points out, the relative weight of these four major European countries in global military spending has dropped by one-third over the last ten years. In 2008 they accounted for 15% of military spending in 2008, but for just over 10% in 2017.

The shift in the world's military centre of gravity is very telling. In 2008, these four European countries together spent 2.6 times more than China. Ten years later, their expenses are a quarter less than China's (78%). 32 ( * )

It is also interesting to compare the combined spending of these four countries with Russia's spending. According to SIPRI, Russia spent $66.3 billion in 2017, which is 15% more than France. If we add to this the expenditures of the four largest EU countries, Russia's military expenditure accounts for a little over one-third of this combined amount (37%). On several occasions during their interviews, your rapporteurs raised the question of this paradox with regard to Russia, a country that is perceived as a great military power but whose spending is lower than that of Saudi Arabia, and falls within the same order of magnitude as the main European armed forces. The paradox was explained in various ways:

- One suggestion was that the numbers we know about only account for a portion of actual military spending. This argument may be valid. Still, it is hard to imagine the difference in values for the official figures going from one to two orders of magnitude. And even if the Russian military effort were in fact twice the estimate made by SIPRI, the figure would remain significantly lower than the figure for the European countries;

- A second and likely more relevant explanation is that the Russian effort is proportionately concentrated in a few high-end domains in which it has traditionally excelled: aeronautics (fighter jets and missiles), 33 ( * ) space, submarines, and of course its nuclear power, in which it remains a force to be reckoned with. Doubtless to this must be added its more recent development of cyberweaponry, which can be considered as a modern version of mathematics, another field in which Russia has long excelled;

- Another point to consider is that members of the armed forces in Russia are in general paid less than members of the armed forces in Europe, which accounts for a significant portion of defence efforts;

- And lastly, compared to other European countries, Russia enjoys a considerable but not quantifiable advantage: unity of command. The Russian army has one commanding authority, one hierarchy, one language, and one equipment range. Obviously, on the operational level, these are very important assets.

3. Europe's rise as a military power has only just begun

The primary mission of States has always been to defend their territory and the people who live there. From a historical perspective, the weakness of the defence effort of the European nations must be seen as a temporary interlude that eventually had to come to an end. Looking back on the interviews and visits they conducted around Europe, your rapporteurs are convinced that for the most part, our European partners are aware of this reality.

It is therefore essential that we see the debate between Atlanticists and defenders of a Europe entirely independent of the United States - and we should emphasise that there are very few of the latter in Europe - for what it is, i.e., as a false debate, and an artificial one at that, more to do with politicians and their personal aims than with real policy issues.

The reality, in fact, is perfectly logical:

- European defence today is dependent upon on the United States;

- The United States is calling for an end to this situation, first of all because they want to be able to concentrate their efforts on their rivalry with China, and secondly because they feel that European countries have benefited from the American presence to obtain substantial savings on their defence budgets;

- The United States and therefore NATO furthermore consider that some of the security challenges Europe is facing are not their responsibility: such would be the case, for example, for immigration crises, or for stabilisation and peacekeeping operations in the European neighbourhood. In the words of one of your rapporteurs' interviewees, “the Mediterranean, Africa and the Middle East will pose major challenges to the security of Europe in the coming decades. But NATO isn't interested, because that's not the purpose it was designed for”;

- European countries are therefore obliged to increase their defence effort;

- But this “burden-sharing” can only be achieved in a gradual and concerted manner amongst the European countries and the United States, so as not to weaken the defence of the European territory.

Thus, far from being in competition with one another, NATO and European efforts in fact converge to ensure the security and defence of Europe. A kind of implicit sharing of roles is in place, which could benefit from some clarification, so as to dispel any fears amongst our partners:

o NATO is responsible for the defence of European territory and the management of high-end threats;

o The European Union and European States acting in intergovernmental frameworks are responsible for ensuring “forward defence,” i.e., interventions outside Europe and security missions, such as migration control or anti-trafficking efforts. It is relevant to point out that the notion that the defence of Europe must include the ability to reach beyond the confines of Europe is not always clearly understood by some of our European partners. Yet one needs only look at the resolute actions taken in the Middle East by Russia to see how the eastern and southern fronts, far from being disconnected, are in fact often linked. The same is true in Africa, which has become a field for fierce competition amongst world powers.

Lastly, the complementary relationship between NATO and the EU is also due to the differences in their members. The most notable of these differences is that NATO includes the participation of Turkey, which for example blocks Cyprus, a member country of the European Union, from becoming a member of the Organisation.

Your rapporteurs propose:

- That the application of the military planning law (LPM) enacted by the Parliament should be safeguarded, particularly in regard to its provision for a rise in defence credits to 2% in 2025, and that the first step towards French participation in European defence should be to confirm our country's commitment to defence;

- That the unproductive notion of an opposition between NATO and the European Union should be abandoned, because they are in fact complementary and not in competition.

* 29 See Senate report no. 562 (2016-2017) by Jean-Pierre RAFFARIN and Daniel REINER: “2% du PIB pour la défense,” p. 13 et seq.

* 30 Only 7 countries now meet or exceed the 2% mark: Greece, Estonia, the United Kingdom, Romania, Poland, Latvia and Lithuania (the latter is at exactly 1.98%).

* 31 The following data are taken from the 2018 report of the Stockholm International Peace Research Initiative (SIPRI), pg. 157 et seq.

* 32 SIPRI 2018, pg. 166.

* 33 Such as the S400 surface-to-air missile systems in particular, and to a lesser extent Russian work in the hypersonic field.