II. THE EU AS A MAJOR STAKEHOLDER IN EUROPEAN DEFENCE: THE NEXT STEP NOW BEING TAKEN

The Treaty of Lisbon, which came into force on 1 December 2009, created the conditions for the strengthening of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP); this paved the way for involvement in the defence domain by the European Commission through the creation of the European Defence Fund.

If sufficiently confirmed by the new EU institutions, these developments will mark a historic turning point.

A. THE EMERGENCE OF THE EU AS A MAJOR STAKEHOLDER IN EUROPEAN DEFENCE

1. Strengthening the common foreign and security policy

The texts have reinforced the Common Foreign and Security Policy, which entered into force in 1993 under the Maastricht Treaty (once known as the “second pillar”), giving it a wider scope and additional tools. On the ground, however, the EU's foreign policy is struggling to take shape and project the image of “Europe as a world power.”

a) Institutional reinforcement of the CFSP/CSDP

The Lisbon Treaty manifestly strengthened the CFSP by creating the post of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Vice-President of the Commission (HR/VP), and the European External Action Service.

Article 42 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) defines the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) as a component of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). It stipulates that the EU may make use of civilian and military assets outside the Union “for peace-keeping, conflict prevention and strengthening international security in accordance with the principles of the United Nations Charter.” The capacities necessary for the accomplishment of these missions are to be provided by the Member States.

Decisions in regard to CFSP/CSDP are to be taken unanimously by the Council, except in specific cases (Article 31 TEU). The adoption of legislative acts (regulations, directives) is excluded.

The Treaty of Lisbon also supplemented the scope of the CSDP resulting from the Petersberg missions, to include joint actions in the disarmament field, military advisory and assistance missions, conflict prevention missions and post-conflict stabilisation operations. All these missions can contribute to the fight against terrorism, as well as by providing support to third countries to fight terrorism on their territory.

In June 2016, the HR/VP presented to the European Council a European Union Global Strategy on Foreign and Security Policy (EUGS). This global strategy identifies five priorities for the Union's foreign policy: the security of the Union, the resilience of the States and societies in the EU's eastern and southern neighbourhoods, the development of an integrated approach to conflict, regional cooperative arrangements, and global governance.

The European Council of 28 June 2016 indicated that it “welcomed with interest” this Global Strategy, which has multiple ramifications (see inset) including the ambition of strategic autonomy for the European Union. The European Council of 15 December 2016 then launched several initiatives to strengthen EU action in the defence domain.

The last report on Global Strategy was delivered at the meeting of the Council on Foreign Affairs held 17 June 2019, at which HR/VP Federica Mogherini presented the third progress report on the EUGS and a report on her activities as HR/VP. In the implementation of this Strategy, France is particularly dedicated to the consolidation of strategic autonomy, understood as greater independence in terms of Union decision-making, assessment, and action, which are necessary in order to enable the European nations to participate in ensuring their own security, contribute to greater burden-sharing, and cooperate on an equal footing with our partners.

|

2016-2018: progress of the CSDP In November 2016, the Council reviewed an “Implementation Plan on Security and Defence”, which was intended to operationalise the vision set out in the EUGS in regard to defence and security issues. To meet the new level of ambition, the plan included 13 proposals, including a Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) focusing on expenditures; a strengthening of the Union's rapid reaction force, in particular by recourse to European Union Battlegroups; and a new, unified Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) for Member States seeking to increase their engagement in security and defence matters. On 30 November 2016, the HR/VP presented the Member States with a European Defence Action Plan (EDAP), containing key proposals for a European Defence Fund dedicated to defence research and the establishment of defence capabilities. The Council also adopted conclusions approving a plan intended to implement decisions on EU-NATO cooperation adopted in Warsaw (42 proposals). These three combined plans, which some have referred to as the “winter package on defence” were a major step forward in the implementation of the Lisbon Treaty in the security and defence domain. In March 2017, the European Council took stock of the progress made, highlighting the creation of the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC), a new structure designed to improve the Union's ability to respond more quickly, more effectively, and more flexibly in the planning and execution of non-executive military missions. It also noted progress made in other domains. For example, in November 2018, it highlighted the substantial progress made over the last two years in areas such as the Civilian CSDP Compact, the development of the MPCC, the implementation of PESCO, CARD, and the European Defence Fund, strengthening cooperation between the Union and NATO, promotion of the proposal for a European Peace Facility, and military mobility. In December 2018, EU leaders also commended the progress made in the areas of ??security and defence, including the implementation of PESCO, military mobility, and the Civilian CSDP Compact. Source: http://www.europarl.europa.eu |

The efficiency and speed of decision-making in the CFSP/CSDP domain is undermined by an institutional barrier: the unanimity rule, which is the focus of regular debate. This rule may be overridden without requiring an amendment to the treaty if the European Council unanimously decides to adopt a resolution providing for the Council to act by qualified majority (Article 31 (3) TEU, known as the “bridging clause”: “The European Council may unanimously adopt a decision stipulating that the Council shall act by a qualified majority...”)

This clause has never been invoked. It is, however, not applicable to decisions with military or defence implications.

In 2017, the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, advocated reducing the systematic use of unanimity on foreign policy issues. In September 2018, the Commission identified three specific areas in which such a change might be made, when it is necessary to:

- respond collectively to attacks on human rights;

- apply effective sanctions;

- or launch and manage civilian security and defence missions.

The nature of the Common Foreign and Security Policy is itself not readily compatible with the qualified majority principle. The idea of ??activating the “bridging clause” provided by the Lisbon Treaty is appealing, as it includes a number of safeguards (prior decision of the European Council, exclusion of the defence domain). But might its implementation be counterproductive if a given country were ultimately to dissociate itself from the common position adopted by qualified majority?

European disunity in the face of the crisis in Venezuela (with Italy, Slovakia, Cyprus and Greece refusing to recognise Juan Guaido as interim president) has recently shown that divisions amongst European partners are possible, even in matters regarding human rights. Likewise, in regard to the implementation of sanctions, it would not seem appropriate to proceed other than by unanimous decision.

Your rapporteurs recommend a flexible approach instead, which would permit those who wish to do so to move forward together within the EU framework (for example: Permanent Structured Cooperation) or outside of it (for example: the European Intervention Initiative). This approach would permit the debate on unanimity, which is a source of tension and thus remains blocked for the time being, to be partly circumvented.

b) Permanent Structured Cooperation: “Sleeping Beauty” awakens

Provided under Articles 42 (6) and 46 of the TEU, Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) has long been the “Sleeping Beauty” 34 ( * ) of the Lisbon Treaty. It was finally launched in December 2017 by 25 of the Member States (out of 27, without Denmark and Malta). The very inclusive German approach prevailed over the French approach to PESCO, which was intended to be more selective and more strictly in line with the provisions of the Treaty, to wit: “Those Member States whose military capabilities fulfil higher criteria and which have made more binding commitments to one another in this area with a view to the most demanding missions shall establish permanent structured cooperation within the Union framework.” (Article 42 (6), TEU).

The initial conception of PESCO was indeed very ambitious - “structured” and “permanent” cooperation was meant precisely to be a plan to integrate military capabilities. In its actual implementation, PESCO is more modest, but it does have the advantage of involving a very large number of States, with each acting according to its own level of industrial know-how and motivation to move forward together. Much to the contrary of the occasional negative commentary asserting that PESCO has been too inclusive and not ambitious enough, your rapporteurs noted that all their interviewees in Europe assessed it positively - which is already a success in itself.

On 6 March 2018, the Council adopted a roadmap for the implementation of PESCO. A list of 17 initial collaborative projects was then adopted. On 19 November 2018, the Council went on to adopt a list of 17 new projects. France participates in 25 of these 34 projects, for 8 of which it serves as coordinator.

It is also important to note that by participating in PESCO, States commit to a number of criteria and to achieving certain military capability objectives.

Your rapporteurs suggest three ways of improving PESCO:

- The primary criticism that might be made of this instrument today is that it does not fit into an organised process of filling Union capability gaps. PESCO has more often tended to focus on industrial returns for Member States rather than on military efficiency as an objective. It needs to be set in the context of a comprehensive plan, developed in a White Paper consistent with NATO planning (see II).

18. - Moreover, a clear reassertion of the obligatory nature of the so-called “more binding” commitments made by the participating States under Protocol no. 10 is necessary. These commitments are listed in the annex to the Council Decision of 11 December 2017 establishing PESCO (see annex). The States agreed on a list of 20 commitments , in which they undertake in particular to increase their investment and research expenditure in the defence domain, take part in a process to identify the EU's military needs, make deployable units available, and develop the interoperability of their forces. The commitments concerning the development of the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) deserve specific mention. These include the following: “increase Europe's strategic autonomy and strengthen the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB)” (Commitment 15); “ensure that all projects with regard to capabilities led by participating Member States make the European defence industry more competitive via an appropriate industrial policy which avoids unnecessary overlap” (no. 19); “Ensure that the cooperation programmes - which must only benefit entities which demonstrably provide added value on EU territory - and acquisition strategies adopted by the participating Member States will have a positive impact on the EDTIB.” (no. 20).

By their participation in PESCO, the States have therefore committed to adopting procurement strategies favourable to the development of the EDTIB.

The texts provide for a mechanism to assess the fulfilment of these obligations by participating States. Sanctions are also possible: under the terms of Article 46 (4) of the Treaty, the Council may exclude a participating State that fails to fulfil its obligations.

If these commitments are not met, there is indeed a risk that PESCO will ultimately fail , as other joint capacity development mechanisms have done in the past. 35 ( * )

- Lastly, the participation of external States is provided for on an exceptional basis as well: such participation would need to be strictly limited to cases where it would permit a substantial contribution to be made, manifestly in the interest of European countries. Such might be the case, for example, if the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) project, which now includes the participation of France, Germany and Spain, were to be included in PESCO and opened to the participation of the United Kingdom.

c) Article 42 (7): inroads by the EU into the joint defence of the continent?

Article 42 (7) of the Treaty on European Union provides a mutual assistance clause between EU countries, established by the Treaty of Lisbon.

|

Article 42 paragraph 7 of the Treaty on European Union “If a Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power, in accordance with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. This shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain Member States. Commitments and cooperation in this area shall be consistent with commitments under the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, which, for those States which are members of it, remains the foundation of their collective defence and the forum for its implementation.” |

This clause has been invoked only once, by France, on 17 November 2015, following the attacks that struck the country on 13 November 2015. The invocation of this clause rather than Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, was an important symbolic gesture. This is particularly the case since the President of the French Republic could instead have chosen to invoke Article 222 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“ The Union and its Member States shall act jointly in a spirit of solidarity if a Member State is the object of a terrorist attack or the victim of a natural or man-made disaster. ”). This article, known as the “solidarity clause,” has a lesser political scope, and does not make use of the concept of “armed aggression” like Article 42 (7) does.

On the other hand, Article 42 (7) of the TEU is not merely symbolic, since it imposes a legal obligation, even though each State is able to privately decide what aid and assistance it can provide.

In response to the activation of this clause , our European partners have made contributions in the Levant (Iraq/Syria) as part of the fight against Daesh, in Mali (strengthening MINUSMA and EUTM Mali, providing tactical transport resources for Barkhane, etc.) and in the Central African Republic (CAR).

|

The Europeans' response to France's activation of Article 42 (7) Many of our partners responded to France's activation of Article 42 (7) of the Treaty on European Union on 17 November 2015. The non-exhaustive list below gives some examples of their contributions. |

|

In the Levant (Iraq/Syria) : on 2 December 2015, the United Kingdom authorised strikes in Syria and doubled its fleet of fighters based in Cyprus; on 4 December, Germany approved operational support for strikes in Syria (1 frigate, 6 Tornados...); the Netherlands authorised an extension of strikes into Syria; Belgium (1 frigate), Denmark, Latvia and Italy (deployment of a CSAR platform, 36 ( * ) i.e., 130 personnel and 1 helicopter) also took measures in support of France. In Mali : reinforcements were provided by several countries to the forces and resources deployed by MINUSMA and EUTM Mali, with tactical transport resources (C130 Hercules) provided to Operation Barkhane (Germany, Belgium, Norway, Austria), and the participation of Norway (though outside the scope of Article 42 (7)) in a logistics base. In the CAR : participation of Portugal in MINUSCA, assignment of troops to EUTM CAR from Poland, Belgium, Spain (within the framework of the Eurocorps). Lebanon : Assignment of a Finnish Infantry Company to the Commander Reserve Force (FCR) as part of UNIFIL (United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon). |

France's invocation of Article 42 (7) of the TEU and the unanimous support it then received constitute an unprecedented affirmation of the solidarity between EU Member States. This allowed France to solicit partners on a bilateral basis to support its operations in the Sahel, thereby facilitating the deployment of Operation Sentinel within the national territory:

“France can no longer do everything on its own. It has had to be engaged in the Sahel, in the Central African Republic, in Lebanon, and in the intervention and response actions in the Levant, while at the same time providing on its own for the security of its national territory. So what we are going to do now is get back to technical discussions with our partners to jointly take stock of what we can do together and what each of us can contribute. That is going to cover this theatre and other theatres, and it is going to be done very quickly,” said Jean-Yves Le Drian, then Minister of Defence, on 17 November 2015.

A feedback analysis needs to be conducted concerning this invocation of the mutual assistance clause. In 2015, the actual implementation of this clause had never really been considered, and the Treaty does not provide any specific roles for the various European institutions in an implementation of Article 42 (7).

Without necessarily seeking to make Article 42 (7) “a kind of enhanced article 5,” 37 ( * ) it might for example be appropriate:

- to plan in advance for the possible cases in which Article 42 (7) could be triggered, and the terms of the assistance to be provided to the country attacked, not only in a bilateral form but also, if appropriate to the case at hand, in the form of EU action (in the field of internal security, border management, CFSP/CSDP, etc.);

- and assign a dedicated information and coordination role to a specific EU body, for example the HR/VP, in case of an activation of Art. 42 (7).

2. A paradoxical decline in missions and operations

The post-Lisbon relaunch of the institutional mechanisms of the CFSP/CSDP has paradoxically been accompanied by a decline in the number of missions and operations undertaken by the EU, which has struggled to demonstrate its added value in this area at a time when the international context would tend to justify an increased commitment.

a) Civil and military missions

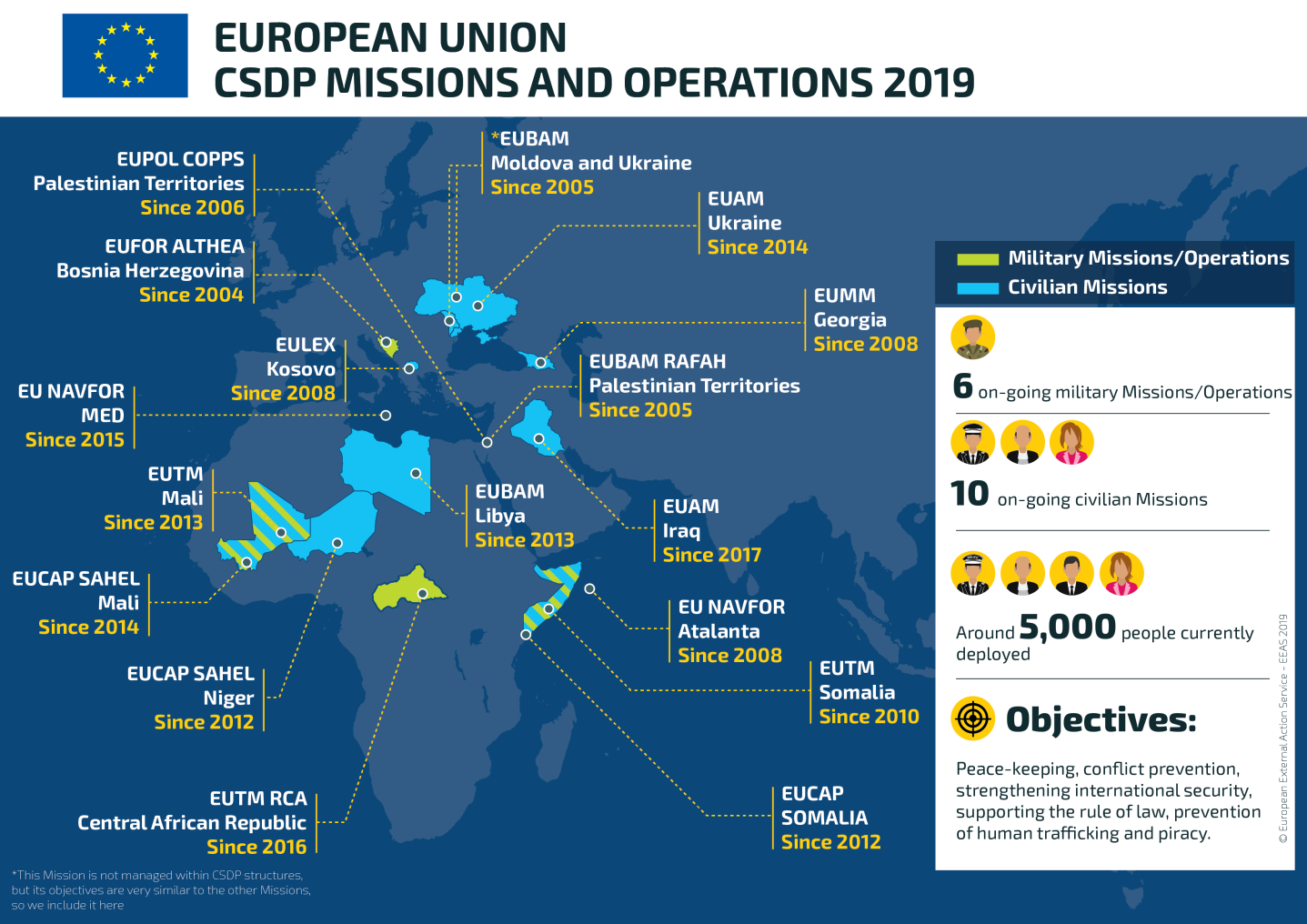

Since 2003, the Member States have launched 33 missions and operations, involving the engagement of nearly 80,000 men and women. As of June 2019, 16 missions or operations are still on-going in Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean, the Balkans and Eastern Europe (see annex to this report). 10 of these missions are civilian and 6 are military. 38 ( * )

Civilian missions focus on the training of third country security forces or on strategic advisory activities. These missions are financed by the EU budget as part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP).

Military operations and missions are funded directly by the 27 Member States participating in the CSDP (all members except Denmark). Some costs are borne on a shared basis via what is known as the Athena mechanism; the contribution made by each State depends on their GDP.

CSDP missions and operations in 2019

Source: European External Action Service (EEAS)

b) A necessary revitalisation

It is clear that the missions and operations of the CSDP are only very partial responses to the current crises.

NATO would appear to be the most appropriate framework for a response to threats from the east. For threats from the south, ad hoc coalitions would appear to be more efficient, and more rapidly deployable. The CSDP would then have more of a supporting role, but would have real added value in Africa and in the Mediterranean, where its inherent global approach would be an asset.

Also of note in this context is the failure, to date, of the EU Battlegroups (EUBGs), which have never been deployed.

After the 1999 meeting of the Council at Helsinki, the European Union set up a rapid reaction force to cope with third country crises, known as the EUBG, or “ battlegroups, ” bringing together 1,500 personnel, deployable in 15 days within the framework of the CSDP. The States provide six-month rotating service for this purpose, with 2 EUBGs theoretically being on duty at the same time in each half-year period.

However, the EUBGs have never been used because of a lack of political consensus, and because of the complexity of their implementation and funding, which runs counter to their original goal of speed and efficiency.

CSDP missions and operations are currently receiving insufficient attention from national and European leaders.

Under the mandate of Federica Mogherini, HR/VP, only three missions and operations have been launched: EUNAVFOR MED (2015), EUTM CAR (2016), and EUAM Iraq in 2017.

For the next Multiannual Financial Framework, the European Commission has proposed the off-budget creation of a “ European Peace Facility ” (EPF) with €10.5 billion , so as to finance the common costs of CSDP operations more effectively. This European Peace Facility is intended to replace the Athena mechanism for the financing of EU operations, as well as the African Peace Facility. It is intended to expand the scope of cost sharing for operations and thus facilitate their deployment. The aim of the EPF is to enable the EU to provide defence assistance to third countries and to international and regional organisations.

The missions and operations of the CSDP will thus need to be relaunched:

- On the one hand, by concentrating resources where the European Union has the highest added value, even if it means accepting the closure of certain missions after an evaluation, since they were in any case not intended to be pursued in the long term;

- On the other hand, by extending the scope of cost sharing and setting up financing mechanisms that are not a hindrance, i.e. by implementing the European Commission's proposal for the European Peace Facility , up to €10.5bn for the duration of the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF).

-Finally, by strengthening the capacities of Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) structure, created in 2017 as part of the EU Military Staff (EUMS) so as to improve EU crisis management structures. This may become the embryo of a veritable European military HQ, the equivalent of NATO's SHAPE, 39 ( * ) which the EU has failed to establish in the wake of the so-called `Pralines' Summit of 2003. 40 ( * ) Such a European HQ would need to be established in line with the resources available to NATO (in keeping with the so-called Berlin Plus agreements).

c) The case of Operation Sophia

The course taken by Operation Sophia is emblematic of a relative decline in CSDP missions and operations.

Your Committee heard Rear Admiral Olivier Bodhuin, Deputy Commander of Operation EUNAVFOR MED Sophia, 41 ( * ) one of CSDP's most significant missions since 2015. This mission, being conducted by 26 EU countries, has a headquarters in Rome, which your rapporteurs visited.

Operation Sophia illustrates the security-defence continuum. In particular, it highlights the importance of a strong link between the EU's actions in the field of security, which is the responsibility of the European Commission, and the CSDP. Since 2015, cooperation has been established between Sophia and the Frontex, Europol and Eurojust agencies. Frontex is an essential partner, which is now gaining ground because of plans to expand the European Border and Coast Guard Agency to 10,000 border guards, including 3,000 EU agents. However, cooperation with EU agencies is currently suffering from a lack of visibility of the future of Operation Sophia.

In March, the EU Council decided to suspend the ships assigned to operation Sophia temporarily because of a failure to reach an agreement on landing ports for migrants. The mission is now concentrating on air patrols, as well as on providing support and training for the Libyan coastguard and the Libyan navy. This unfortunate suspension of the operation's maritime resources deprives the mission of its information sources and capacity to act and prevents it from implementing the arms embargo against Libya.

Although the continuation of Operation Sophia is certainly to be welcomed, its decline is particularly regrettable at a time when the EU needs to ensure the maximum mobilisation of all its resources in the face of challenges that are likely to be significantly heightened in the future. But any rebound of Operation Sophia would obviously need to take place through the resolution of the difficult issues surrounding migrant landing and processing ports.

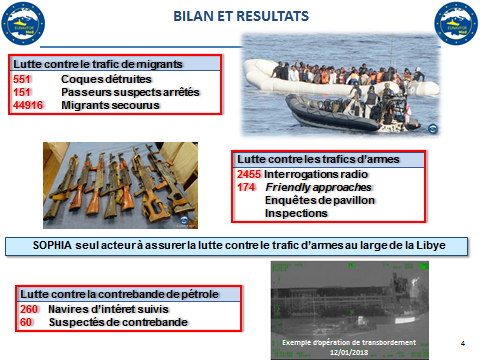

Operation Sophia has achieved tangible results, as shown in the overview below.

Review of EUNAVFOR MED operation SOPHIA (June 2019)

REVIEW AND RESULTS

Efforts to combat arms smuggling

SOPHIA is the only operation combatting arms smuggling off the Libyan coast

Radio contacts

Friendly approaches

Flag enquiries

Inspections

Example of transhipment operation

Vessels of interest tracked

Suspected of smuggling

Vessels destroyed

Suspected smugglers arrested

Migrants rescued

Efforts to combat oil smuggling

Efforts to combat migrant smuggling

Source: EUNAVFOR MED

* 34 “Permanent Structured Cooperation. National Perspectives and State of Play,” study by Frédéric Mauro and Federico Santopinto, produced for the European Parliament Subcommittee on “Security and Defence,” July 2017.

* 35 “Moving PESCO forward: what are the next steps?”, Jean-Pierre Maulny, Livia Di Bernardini, IRIS, ARES, May 2019.

* 36 Combat Search and Rescue.

* 37 Expression used by Emmanuel Macron, President of the French Republic, in Helsinki on 30 August 2018.

* 38 EUTM Mali, EUTM Somalia, EUTM CAR, EUNAVFOR MED Sophia, EUNAVFOR Atalante, EUFOR Althea (Bosnia-Herzegovina).

* 39 Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe.

* 40 Summit of the leaders of France, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg held in Brussels in April 2003. During this summit, States opposed to the Iraq war had expressed the desire to create a “hub” for the joint planning and conduct of operations. The UK opposed this until the 2016 referendum approving the Brexit.

* 41 Hearing conducted 26 June 2019.