PART ONE - THE EUROPEAN UNION AS THE SECOND PILLAR OF EUROPEAN DEFENCE: A HISTORIC TURNING POINT TO ENSURE THE SECURITY OF EUROPEAN CITIZENS

The work done by your rapporteurs follow on from your Committee's previous information report on the same subject, entitled “ Pour en finir avec `l'Europe de la défense' - Vers une défense européenne ”, dated 3 July 2013. 4 ( * ) This report denounced the notion of a “Europe of Defence” as a conceptual dead-end that must urgently discarded by building a real “ European defence, ” which it deemed an “ imperious necessity .”

Despite undeniable progress made towards a European defence in recent years, this observation remains a topical one.

I. EUROPEAN COUNTRIES PROVIDING FOR THEIR OWN DEFENCE: A NECESSARY AMBITION

A. A REALITY: THE UNITED STATES STILL PLAYS A PREPONDERANT ROLE IN THE DEFENCE OF THE EUROPEAN CONTINENT

If “European defence” is understood to refer to all the military resources able to be implemented jointly or in a coordinated manner by the countries of the continent, whether within the framework of the European Union or outside it, then it is clear that this European defence plays only a secondary role in the collective defence of Europe today.

1. The slow gestation of European defence poses no challenge to the preponderant role of the Americans

The history of European defence began with a resounding failure: that of the European Defence Community (EDC), rejected by France on 30 August 1954. It marked the failure of the idea of a “European army”: the treaty signed on 27 May 1952 5 ( * ) was intended to establish “a European defence community, supranational in character, consisting of common institutions, common armed forces and a common budget” (Article 1). This European army, placed under the command of NATO, was to provide a way to permit the rearmament of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG).

The idea of ??a European army has never recovered from this initial failure and seems unlikely to do so any time in the near future.

a) The birth of European defence...

After the Second World War and throughout the Cold War, in the face of the Soviet threat, Western Europe placed itself under the protection of the United States. The interests of these two entities (Western Europe and the United States) were very close at the time, even identical, and in the aftermath of the war, their respective resources were completely out of proportion.

The establishment of the Western European Union (WEU) by the Paris Accords (1954), in the wake of the Western Union established by the Brussels Treaty (1948) and after the failure of the European Defence Community (EDC), did not bring this into question. Always in the shadow of NATO, in spite of a certain revitalisation in the 1980s, the WEU remained in the background until it began to be rivalled in the pursuit of its objectives by the European Union, which finally prevailed, since the WEU was ultimately dissolved in 2011.

After the Cold War, the question of the collective defence of the territory and population of the European continent retreated to the background with the collapse of the Soviet bloc, in the absence of a clearly identifiable threat.

This strategic breakthrough enabled the (at least provisional) emergence of the components of a new security architecture, as illustrated by:

- The creation of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) : took over in 1994 from the Conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) which had been created by the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference (1975). The end of the Cold War seemed to have opened a new era of cooperation: “ the era of confrontation and division in Europe is over, ” 6 ( * ) was the belief at the time.

- The signing of a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between the European Union and Russia (1994);

- The establishment of cooperation between NATO and Russia , which resulted in the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997 and the creation of the NATO-Russia Council in 2002.

At the same time, however, European countries were made acutely aware of the need to be able to intervene in their immediate environment, and possibly to do so without the Americans.

The wars in Yugoslavia , which killed about 150,000 people in 10 years (1991-2001) on the European Union's doorstep, were quite revealing in regard to Europe's inability to act outside NATO , i.e., without the United States. The agreements that ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1995 were signed at Dayton, in the United States, symbolising the paralysis of the European countries in the face of the biggest conflict waged on the continent since the end of the Second World War. And once again, it was ultimately the intervention of NATO that put an end to the war in Kosovo twenty years ago.

This collective European failure was the shock that led to the emergence of a common security and defence policy for the EU in the 1990s.

It took a major crisis with a considerable cost in human lives to allow some slow progress to be made and that progress is still incomplete, despite other crises that have given rise to phases of acceleration (Crimea, Ukraine).

While it may be legitimate for progress to be made in this way, in response to each successive crisis revealing the changes in the strategic environment, it would nevertheless be desirable to anchor the ambition for an autonomous European defence in a robust long-term process, and not to wait for another major crisis to erupt on the continent in order to achieve tangible results.

In 1992, with the Petersberg Declaration, the countries of the Western European Union (WEU) decided it would be possible to conduct certain military missions with a limited scope, acting in co-operation with NATO or the EU. These so-called “ Petersberg ” missions include the following:

- humanitarian missions or evacuation of nationals;

- peacekeeping missions;

- missions undertaken by combat forces for crisis management, including peace-making operations.

The Maastricht Treaty, which came into force in 1993, introduced the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) as the second pillar of the EU. In particular, the Amsterdam Treaty (1997) assigned to the CFSP the “progressive framing of a common defence policy, which might to lead to a common defence,” with the objective of carrying out Petersberg missions: ”Questions referred to in this Article shall include humanitarian and rescue tasks, peacekeeping tasks and tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peace-making.” (Article 17 of the Treaty on European Union in force at the time).

So since the 1990s, Europe has sought to organise itself so as to be able to manage crises on its own by acquiring a “ capacity for autonomous action ,” 7 ( * ) also referred to as an “ operational capacity ” (Article 42 TEU). It has thus gradually built up an ambition for “ strategic autonomy. ” 8 ( * )

In spite of the clause stipulating solidarity amongst European countries established under Article 42 paragraph 7 of the Treaty on European Union (see below), this “strategic autonomy” remains a limited concept. Article 42 of the Treaty on European Union, which has replaced and supplemented Article 17, makes clear, indeed, that “the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation [...] for those States which are members of it, remains the foundation of their collective defence and the forum for its implementation.”

In the course of their travels, your rapporteurs noted that in all the countries they visited, 9 ( * ) it was considered obvious and necessary for NATO to be the cornerstone of European collective defence.

b) ...in no way questioned the preponderant role of NATO...

During the Cold War, NATO devoted itself to its core mission: collective defence, on the basis of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty signed in Washington in 1949, which recently had its seventieth anniversary. This clause, which states that an attack against one of the allies is an attack against all of them, has been invoked only once: by the United States, after the attacks of 11 September 2001. At the time when this Treaty was signed in Washington, the signatory member countries wished to ensure that the United States would automatically come to their aid if one of the signatories were ever attacked. But the United States opposed the notion of automatic action, and thus Article 5 was drafted accordingly.

|

Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty “The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all; and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognised by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area. “Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall immediately be reported to the Security Council. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security.” |

The NATO Strategic Concept (2010) reaffirmed the strength of this commitment: “NATO members will always assist each other against attack, in accordance with Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. That commitment remains firm and binding. NATO will deter and defend against any threat of aggression, and against emerging security challenges where they threaten the fundamental security of individual Allies or the Alliance as a whole.”

This collective defence is ensured up to and including at the nuclear level , with a preponderant role assigned to the American deterrent force, and complementary roles to the French and British deterrent forces: “The supreme guarantee of the security of the Allies is provided by the strategic nuclear forces of the Alliance, particularly those of the United States; the independent strategic nuclear forces of the United Kingdom and France, which have a deterrent role of their own, contribute to the overall deterrence and security of the Allies.” 10 ( * )

The activities of the Alliance were diversified after the end of the Cold War (collective defence, crisis management and security cooperation), but are now being refocused on collective defence so as to confront the “arc of instability” at its periphery.

From the outset, there has been an implicit sharing of tasks in relations between the EU and NATO. The 1998 French-British Saint-Malo declaration already emphasised the ability of the European Union to act “ where the Alliance as a whole is not engaged ” via “suitable military means (European capabilities pre-designated within NATO's European pillar or national or multinational European means outside the NATO framework).” 11 ( * ) The role of the EU in the defence domain was therefore conceived from the outset as complementary, or , one might say, even subsidiary to NATO , so as to avoid any unnecessary duplication of efforts.

The “Berlin Plus” arrangements (2003) consolidated this complementarity, permitting the EU to use NATO planning and operational capabilities in operations in which NATO is not engaged as such. It was on the basis of these arrangements that the NATO operation in Macedonia was transferred to the European Union starting in April 2003, as was NATO's operation in Bosnia and Herzegovina at the end of 2004.

The 2016 Warsaw NATO Summit resulted in an enhancement of EU-NATO relations, on a more balanced basis than had been established under the “Berlin Plus” agreements. This summit led to the adoption of a joint EU-NATO declaration, 12 ( * ) followed by the adoption of 74 common measures in 7 areas of cooperation (hybrid threats, operations, cybersecurity, capabilities, research, exercises, assistance to third countries). This development confirmed, however, that the continent's collective defence, or, for that matter, what is known as “high-spectrum” defence, is primarily a matter for NATO:

“Furthermore, although what I'm going to say isn't written in it, this joint declaration has indeed reaffirmed three basic principles: collective defence is mainly the responsibility of NATO; there will be no European army; and there will be no duplication of the command structures established within NATO. These principles were consistently brought up in every meeting held amongst the Defence Ministers, which NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and European High Representative Federica Mogherini were mutually invited to attend. These principles are laid out in the minutes. They form the basis of cooperation between NATO and the European Union.” 13 ( * )

|

EU-NATO relations 2001 marked the beginning of institutionalised relations between NATO and the EU, based on the measures taken in the 1990s to promote greater European responsibility in the defence field (co-operation between NATO and the Western European Union). The NATO-EU Declaration on European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) adopted in 2002 defined the political principles underlying the relationship, and confirmed that the EU would have guaranteed access to NATO planning capabilities for purposes of its own military operations. In 2003, the “Berlin Plus” arrangements established the foundations necessary for the Alliance to support EU-led operations in which NATO as a whole was not engaged. At the 2010 Lisbon Summit, the Allies emphasised their determination to strengthen the NATO-EU strategic partnership. With the 2010 Strategic Concept, the Alliance committed to working more closely with other international organisations to prevent crises, manage conflicts, and stabilise post-conflict situations. In July 2016 in Warsaw, the two organisations prepared a list of areas in which they sought to intensify their cooperation, given the common challenges facing them to the east and south: combating hybrid threats, increasing resilience, defence capacity building, cyber-defence, maritime security, exercises, etc. In December 2016, NATO Foreign Ministers endorsed 42 measures aimed at furthering cooperation between NATO and the EU in those areas. Further areas of cooperation were decided upon in December 2017 as well. NATO and the EU currently have twenty-two members in common. Source: www.nato.int |

This implicit “sharing of tasks” that is inherent to the EU-NATO strategic partnership, even if it is merely a didactic simplification, remains useful today, based on certain standard ideals, especially those of “collective defence” and “crisis management.” The boundary between collective defence, crisis management and security cooperation (the three missions of NATO) has indeed been blurred, along with the distinction between State and non-State threats.

c) ...nor the role of the United States as Europe's defence partner

The United States does not provide “90 per cent” of the NATO budget, as US President Donald Trump has claimed, but “only” 22.1 per cent of the organisation's budget. The other two primary contributors are Germany (14.7%) and France (10.5%).

But above all, the United States reproaches European countries for not progressing quickly enough towards NATO's 2024 targets - military spending increased to 2% of GDP, 20% of which is to be allocated to major equipment - which supposedly makes them “freeloaders” (the President of the United States would even have preferred this effort to be increased to 4%).

The United States, meanwhile, devotes 3.4% of its GDP to defence, i.e., $605 billion, which is equal to two-thirds of the military expenditure of all NATO countries combined , 14 ( * ) and about one-third of the worldwide total for all military budgets. In 2018, defence spending in the United States was increased by an amount (+$44 billion) itself equivalent to Germany's entire defence budget.

Within this gigantic US military budget, spending specifically devoted to the defence of Europe is estimated at $35.8 billion in 2018, 15 ( * ) or 6% of the total... which is almost as much as the entire defence budget of France (€35.9 billion in 2019).

These expenses are divided between:

- Financing the US presence on the European continent ($29.1 billion), i.e., 68,000 personnel from the five branches of the US military, including about 35,000 in Germany, where the United States European command is located (EUCOM Stuttgart). For the record, in the 1960s there were 400,000 US Army personnel in Western Europe, and 200,000 still in the 1980s.

- The American contribution to NATO ($6.7 billion).

Since 2014, as part of assurance measures implemented by NATO, the United States has increased its presence in Europe via a budget programme known as the “European Deterrence Initiative” (EDI), 16 ( * ) which has provided it with funding for Operation “ Atlantic Resolve, ” (OAR) in favour of the countries of Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania).

The funding of the EDI has steadily increased, from $1bn in 2014 to $6.5bn in 2019. This budget is devoted to strengthening the rotating presence of American forces in Europe, military exercises, the improvement of pre-positioned infrastructure and equipment and, lastly, the strengthening of partner countries' capabilities.

Of course, these figures do not cover all the resources that the United States earmarks for the protection of Europe.

Other aspects of the American contribution to the defence of Europe merit mention here as well:

- As noted above, the United States plays a special role in NATO's strategic nuclear capability , while the United Kingdom and France play complementary roles (France has no nuclear weapons assigned to NATO and is not a member of NATO's Nuclear Planning Group). 17 ( * )

Furthermore, “nuclear sharing” arrangements are in place, which provide for US tactical nuclear weapons to be stationed in several European countries. Though this information is not public knowledge, 5 NATO countries are generally considered to be host countries for these nuclear weapons: Germany, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey. The number of weapons stored in these countries is estimated at 140. As a reminder, during the Cold War, when the United Kingdom and Greece were also host countries, the estimated number of these weapons on the continent exceeded 7,000. The weapons currently in place are B61 bombs. They are intended for use by the air forces of the host country with the agreement of the United States and the host country (via the double-key principle).

More precisely:

“On most of the bases, the weapons are stored under the responsibility of US support units. Bomber fighters from the host country are assigned and pilots trained to deploy these free-fall weapons if the decision is made to use them. Germany thus maintains its 33 rd Fighter Bombers Squadron for this mission, equipped with Tornado PA-200 aircraft. The Netherlands and Belgium have dedicated F-16 crews (10 th Tactical Wing for Belgium, 312 th and 313 th Squadrons of the RNAF). In Italy, the Tornado PA-200s of the 6 th Stormo wing have the capacity to carry B61s as well. At Aviano (Italy) and Incirlik (Turkey), it would a priori be American planes that would be responsible for carrying these weapons.” 18 ( * )

This issue of nuclear sharing is fundamental in an analysis of the procurement policies of the air forces of the countries concerned and, for the future, for the scaling of the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) project.

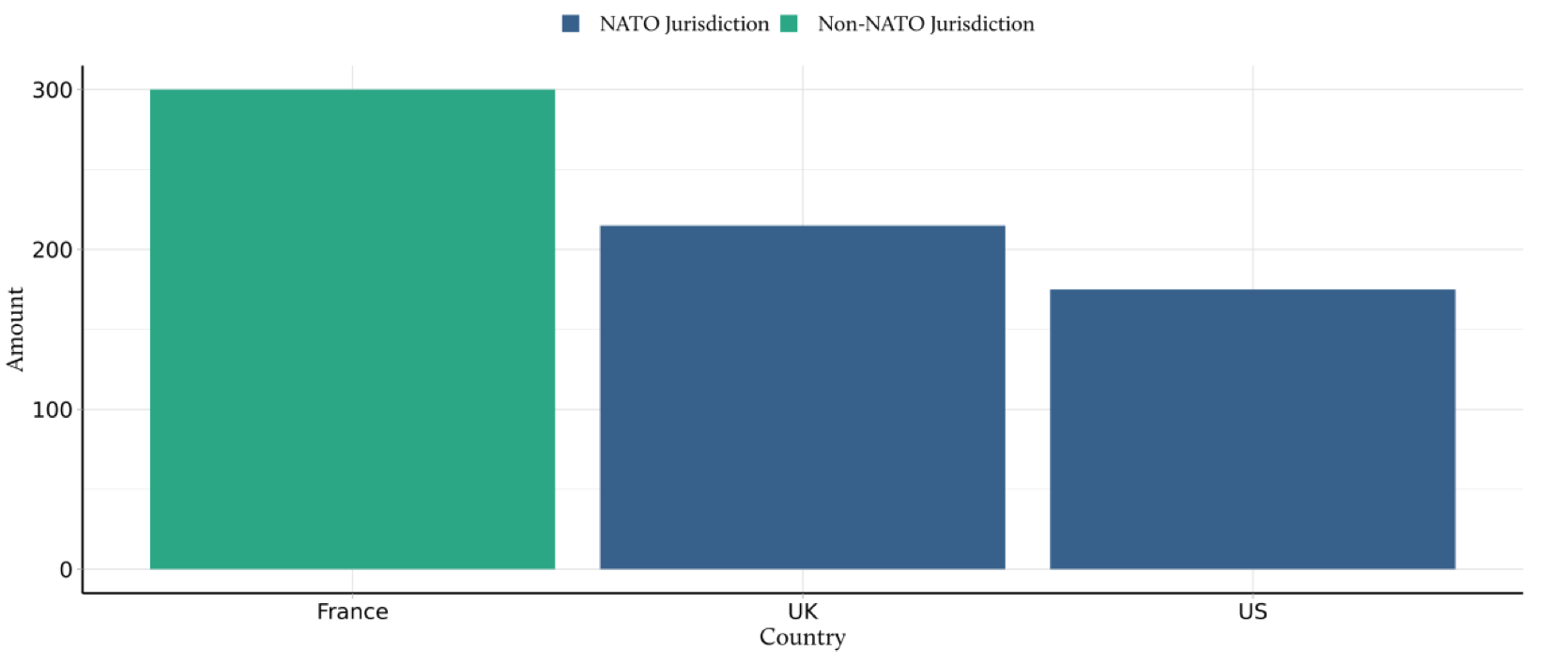

Estimated number of nuclear weapons in Europe (2018)

Source: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (as per SIPRI).

- At the request of the United States, NATO is gradually deploying a ballistic missile defence system. This is intended as a response to the Iranian threat and has contributed to a deterioration of relations with Russia. The system includes a major American contribution, decided on in 2009: 19 ( * ) a radar system in Turkey, sites in Romania and Poland, and 4 AEGIS anti-missile frigates based in Spain.

- American supremacy is particularly noticeable in certain areas: strategic transport, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (heavy drones in particular), and refuelling.

Finally, a study was conducted that estimated the cost of the investments that NATO countries would have to make on the purely theoretical assumption of a United States exit from the Organisation , in order to be able to respond to two particular conflict scenarios: 20 ( * )

- 1 st scenario: a challenge to the security of European sea lanes : in this case, the capacity deficit generated by the departure of the United States from NATO would force the European countries to invest between $94 billion and $110 billion to provide for their own maritime security;

- A scenario in which Article 5 is triggered in the context of a conflict on the Eastern flank of NATO (occupation by Russia of Lithuania and part of Poland). 21 ( * ) In this case, to be able to deal with the situation, the European NATO members would have to invest between $288 billion and $357 billion to fill the capacity gaps created by an American withdrawal.

These amounts are not unachievable , since if European NATO countries were to meet the 2% of GDP target, they would already be spending an additional $102 billion per year.

This study thus highlights the implications of the debate on strategic autonomy. It suggests that the debate be refocused on the issue of capability gaps rather than on institutional mechanisms.

“As for the strategic autonomy that France seeks,” said many of our interviewees, “ nobody knows what it means. ” Autonomy does not mean strategic independence; it is a relative notion, in itself insignificant without a definition of the degree of autonomy sought, the investments to be used to achieve that autonomy, and the timetable for its attainment - in other words, unless there is a roadmap for strategic autonomy.

Ultimately, many of our European partners share the opinion of Wolfgang Ischinger, President of the Munich Security Conference:

“There have been lots of sound bites about the strategic autonomy of Europe. But I don't think it's the right way to go. Our reliance on US military capabilities is absolutely necessary for the security of Germany and Europe in the short, medium and long term. We are blind, deaf and powerless without our American partner.” 22 ( * )

2. This is a reality that France must take into account, despite its unique situation in Europe

In view of this dependence on the Americans, France appears as an exception within its environment, having been building its defence apparatus since the 1960s with the aim of national independence.

a) The end of the “French exception” in NATO

When it was created, France actively supported NATO so as to definitively involve the United States in the defence of Europe and thus preserve peace. The headquarters of NATO was then set up in France, until General de Gaulle's 7 March 1966 decision to cease France's participation in the Organisation's integrated command structure whilst still remaining within the Alliance.

This unique situation came to an end in 2009, when President Nicolas Sarkozy decided to restore France's participation in the integrated structures with the notable exception of the Nuclear Planning Group .

Thus, “by its return to the NATO Integrated Military Command in 2009 while preserving its special status in the nuclear domain, France fully acknowledged NATO's role in European defence.” 23 ( * )

President François Hollande maintained this approach. In 2012, in a report 24 ( * ) on this subject, Hubert Védrine, former Foreign Affairs Minister, took the position that a new exit was not possible, whatever the benefits of France's return to NATO's integrated command, which he deemed to be mixed:

“France's (re)exit from the integrated military command is not an option. Nobody would understand it in the United States or in Europe, and it would not give France any new leverage - quite the contrary in fact. It would instead ruin any possibility France has for action or influence with any other European partner in any area whatsoever. Furthermore, from 1966 to 2008, that is, in more than 40 years, not a single European country ever expressed support for France's position on independence.”

If a certain French exception still remains in NATO, it has only to do with the status of our deterrent force.

b) Strategic autonomy and nuclear deterrence

Of all the countries of the European Union and the European partners of NATO, France is the only one to pursue an aim of national independence within the framework of defence cooperation, although without ruling out certain interdependencies, as underlined in the Defence and National Security Strategic Review of December 2017.

Even the United Kingdom, also a nuclear power and our most similar partner within Europe, has seen its striking force as being closely linked to that of the United States and the NATO framework since the 1962 Nassau Agreement.

This significant difference in strategic culture is a parameter that must be taken into account in the dialogue on strategic autonomy at the European level.

Semantics is a problem in itself. The term “ deterrence ” is not understood the same way everywhere in Europe: in NATO, for example, this concept refers to a set of measures, in the conventional field as well, that are intended to require any adversary to face risks that will outweigh any potential gain. In German, the word “ Abschreckung ” (deterrence), which is associated with the words “fear” and “fright,” has a very negative connotation. European public opinion is generally not very familiar with the French concept of deterrence, i.e., the idea of ??defensive nuclear weapons, the purpose of which is to inflict damage that would be unacceptable to the enemy, one of the characteristics of which is that they are always ready to be used, so that they will never have to be used. In this sense, nuclear arms are a fundamentally political weapon.

“For France, nuclear arms are not intended to gain an advantage in a conflict. Because of the devastating effects of nuclear weapons, they have no place in any offensive strategy; they are seen only as part of a defensive strategy. Deterrence is also what permits us to preserve our freedom to act and make decisions under all circumstances (...). It is the supreme responsibility of the President of the Republic to constantly assess the character of our vital interests and of any attacks to which they may be subject.” 25 ( * )

In 1992, however, President François Mitterrand did raise the question of the relationship between French deterrence and European defence, asking, in the aftermath of the Maastricht Treaty: “Would it be possible to imagine a European doctrine (of deterrence)? That is going to be one of the big questions in terms of building a common European defence.”

In 1995, at the Chequers Summit , France and the United Kingdom jointly affirmed that any situation that might arise threatening the vital interests of either one of their two nations would be considered a threat to the vital interests of the other as well. 26 ( * )

The issue was brought up time and again in the following years by all the Presidents of the French Republic:

- Jacques Chirac: “The development of the European Security and Defence Policy, the growing integration of the interests of the countries of the European Union, and the solidarity that now exists between them, make the French nuclear deterrent, by its mere presence, an essential element in ensuring the security of the European continent.” (Ile Longue speech, 19 January 2006);

- Nicolas Sarkozy: “It is a fact that by their mere presence, French nuclear weapons are a key part of Europe's security. Any aggressor that might consider challenging Europe would have to take them into consideration.” (Cherbourg speech, 21 March 2008);

- And François Hollande as well: “The definition of our vital interests cannot be limited simply to the national level, because France does not see its defence strategy as existing in a vacuum, even when it comes to nuclear arms. We have expressed this position many times to the United Kingdom, with which we have established an unparalleled degree of cooperation. We are participating in the European project, and have built a community of destiny with our partners; the existence of a French nuclear deterrent makes a strong and essential contribution to Europe. Furthermore, France stands in solidarity with its European partners, a solidarity that is both in fact and in feeling. Who then could ever dream that any attack seeking to threaten the survival of Europe would have no consequences? That's why our deterrent force goes hand in hand with the constant strengthening of the Europe of Defence. But our deterrent force ultimately belongs to us alone - it is we who make the decisions about it, and it is we who must assess the state of our own vital interests.” (speech given at Istres, 19 February, 2015).

Your rapporteurs asked about the European aspect of the French deterrent force in the European countries they visited, for example by framing the question as follows: By advocating strategic autonomy for Europe, is France seeking to place all its partners under its “nuclear umbrella”? While pointing out the abovementioned statements, tending to give a European dimension to what are identified as the “vital interests” of France, your rapporteurs also reminded the interviewees of the fundamental principles underlying the French deterrent force, a component of our national sovereignty, the deployment of which is exclusively its own responsibility, and must remain the sole prerogative of the President of the French Republic.

Although rarely debated in France, the idea of ??the Europeanisation of the French deterrent force is nevertheless gaining momentum around Europe , though there is no consensus on the matter. The proponents of this course of action suggest that it might be possible to permit “double key” nuclear sharing arrangements with France on the model of those now in place with the United States, or to institute a contribution from Germany, or from a group of several EU countries, to help provide funding for the French deterrent force. 27 ( * ) In 2017, the services of the Bundestag determined that strictly from a legal perspective there would be no obstacles to the potential establishment of such a financial contribution.

Wolfgang Ischinger, chairman of the Munich Security Conference, believes for his part that sharing the financial burden of deterrence would not be incompatible with maintaining the current pattern where deployment is exclusively under the authority of the President of the French Republic:

“In the medium term, the question of a Europeanisation of French nuclear potential is indeed a very good idea. It is a matter of knowing if and how France might be willing to strategically place its nuclear capacity at the service of the European Union as a whole. Concretely speaking: the options for an engagement of nuclear force by France would need to cover not only its own territory, but also the territory of its partners in the European Union. In return, we would need to define what the European partners could bring to the table for this purpose, so as to achieve a fair distribution of contributions. However: any possible use of nuclear weapons could not ultimately be decided by an EU committee. This decision would need to remain up to the French President. And we would have to accept that responsibility! ” 28 ( * )

It is nevertheless quite premature to discuss any possible sharing by France of its nuclear deterrent force. The voices that have been raised in this regard are alone and are not representative of any majority of political forces or public opinion amongst our European partners.

It must be borne in mind, however, that for a number of observers, particularly in countries that rely on the supreme guarantee of US nuclear forces, such a debate might be considered to follow logically as a consequence of France's active engagement in favour of the strategic autonomy of the EU.

* 4 An information report by Daniel Reiner, Jacques Gautier, André Vallini and Xavier Pintat, co-rapporteurs, as part of a working group also including the participation of Jean-Michel Baylet, Luc Carvounas, Robert del Picchia, Michelle Demessine, Yves Pozzo di Borgo and Richard Tuheiava, Senators.

* 5 Draft Treaty signed by the Governments of Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the Federal Republic of Germany.

* 6 Charter of Paris for a New Europe (1990).

* 7 Franco-British Declaration on European Defence: Saint-Malo, 4 December 1998.

* 8 “A Global Strategy on Foreign and Security Policy for the European Union,” European External Action Service (2016).

* 9 Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, United Kingdom.

* 10 Strategic Concept (2010).

* 11 Franco-British Declaration on European Defence: Saint-Malo, 4 December 1998.

* 12 Joint declaration by the President of the European Council, the President of the European Commission and the Secretary General of NATO, 8 July 2016.

* 13 General Denis Mercier, former NATO Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (hearing before the National Defence and Armed Forces Committee of the National Assembly, 5 March 2019).

* 14 The total military expenditure of all NATO countries in 2018 amounted to $919 billion (source: NATO, 14 March 2019).

* 15 Source: “On The Up: Western Defence Spending in 2018,” Lucie Béraud-Sudreau, International Institute for Strategic studies (IISS, 2019).

* 16 This programme was previously known as the “European Reassurance Initiative” (ERI).

* 17 Since the Nassau Accords between the United States and the United Kingdom (1962), British nuclear capability has been closely linked to that of the Americans and to the NATO framework, as the National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 makes clear .

* 18 “Forces aériennes européennes et mission nucléaire de l'OTAN” , Emmanuelle Maitre, research fellow at the Strategic Research Foundation (FRS), Défense & Industries no. 13 (June 2019).

* 19 US European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA).

* 20 ”Defending Europe: Scenario-Based Capability Requirements for NATO's European Members,” The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS, April 2019).

* 21 The study does not comment on the validity or plausibility of the scenarios considered.

* 22 Interview with Wolfgang Ischinger, president of the Munich Security Conference, Ouest-France, 9 February 2019.

* 23 Defence and National Security Strategic Review (2017).

* 24 Report by Hubert Védrine to the President of the French Republic on the consequences of France's return to NATO's integrated military command, the future of transatlantic relations, and the prospects for a Europe of Defence (14 November 2012)

* 25 Speech of the President of the Republic on nuclear deterrence, given at Istres on 19 February 2015.

* 26 Chequers Summit (30 October 1995).

* 27 See for example: “NATO Nuclear Sharing and the Future of Nuclear Deterrence in Europe,” The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (2018).

* 28 Ouest-France, 9 February 2019.