PART TWO - FAR FROM THE UTOPIAN GOAL OF A “EUROPEAN ARMY”: A DYNAMIC THAT MUST REMAIN FLEXIBLE AND PRAGMATIC

I. TWO MAJOR PARTNERS: THE UNITED KINGDOM AND GERMANY

A. INTEGRATING THE UK, A VITAL PARTNER

Of all our European defence partners, the United Kingdom is likely the one whose concerns are most similar to our own. While Brexit has created a climate of uncertainty, weighing even on our bilateral relationship, it is urgent that we intensify our strategic dialogue and consolidate and develop our cooperation in the armaments field.

1. A context marked by the uncertainties of Brexit

a) A leap into the unknown?

The United Kingdom introduced the principles underlying the CSDP together with France at the Saint-Malo Summit (1998). After the Iraq war, however, when the CSDP appeared as a possible counterbalance to the power of the United States, it began to distance itself from those principles. Atlanticists first and foremost, the British then acted to restrain a number of steps forward, such as the establishment of a military planning and conduct capability for the EU, which was only able to come to fruition after the Brexit referendum of 2016.

The withdrawal agreement negotiated between the EU and the UK government devotes few words to defence issues. It does stipulate that the provisions on CFSP/CSDP will cease to apply to the United Kingdom if both parties reach an agreement governing their future relations in this domain during the transitional period.

In addition, the political declaration that accompanies this withdrawal agreement, mentions the need for a future partnership that is “ ambitious, close and lasting ” in the field of foreign policy, and for “ flexible and scalable cooperation. ” “The future relationship should (...) enable the United Kingdom to participate on a case by case basis in CSDP missions and operations through a Framework Participation Agreement.”

According to the political declaration, the UK should be permitted to participate in certain EU programmes and agencies as far as possible under the terms of EU law, thus allowing the United Kingdom to participate, for instance, in projects of the European Defence Agency (EDA), the European Defence Fund (EDF) and Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). Arrangements have also been discussed in regard to the space field.

With the House of Commons having rejected the withdrawal agreement on three occasions, and the EU having indicated that no renegotiation is possible, though amendments to the political declaration may be, the prospect of a “hard Brexit” is becoming more and more credible. But a “hard Brexit” would obviate all the provisions of the abovementioned withdrawal agreement and political declaration - it would be a leap into the unknown.

And the uncertainties are all the greater as British leaders and public opinion are tempted to turn more to the rest of the world than to Europe , with the United Kingdom aiming to assert itself as a global power (“Global Britain”). Former defence minister Gavin Williamson, for example, stated: “[There are] those who believe that, as we leave the European Union, we turn our back on the world. But this could not be further from the truth. We will build new alliances, rekindle old ones and most importantly make it clear that we are the country that will act when required.” 54 ( * ) In courting public opinion, supporters of Brexit have thus played upon the public's nostalgia for the bygone power of the British Empire.

To the uncertainties generated by Brexit, we must also add the uncertainties that weigh upon the British defence apparatus. A recent parliamentary report 55 ( * ) showed that the British Ministry of Defence did not have a sufficient budget for its equipment procurement and support plans. The gap between its available budget and its cost requirements is estimated at between £7bn and £14.8bn over 10 years. Budgetary risks could also increase, due to the possible negative economic consequences of Brexit.

b) A shift in the balance of relations at the EU

The exit of the United Kingdom upsets the balance of relations amongst EU nations, which is particularly delicate in the areas of foreign policy and defence.

Brexit will essentially deprive the European Union of the Member State with the largest defence budget (£45bn, or 2.15% of British GDP 56 ( * ) ), and of a nuclear power with a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).

The exit of the United Kingdom also strips France of what is now its most kindred and closest partner in the Union, both in terms of military capabilities and the ability to conduct high-intensity extraterritorial operations.

As a result, France will become the only EU country both possessing nuclear weapons and holding a permanent seat on the UN Security Council, thus giving it greater responsibility and also putting it at risk of being subjected to greater pressures, for instance advocating the notion that it should share its seat at the UNSC with the rest of the EU. Certain voices have been raised to such effect, particularly in Germany. 57 ( * )

This is not a desirable development. It would be neither in our interest nor in that of the Union. The EU currently holds five seats (2 permanent and 3 non-permanent) and it is unclear what benefit could be obtained from trading those 5 seats for one, even if permanent. In the absence of a unified foreign policy, there would be a risk that the EU representative would all too often abstain from votes.

This is why France is opposed to the notion, and argues instead for the admission of Germany as a permanent member of the UNSC.

2. The need to invent “creative” partnership arrangements

In September 2017, Prime Minister Theresa May asked negotiators to find “creative” solutions to involve the UK in the CFSP/CSDP.

a) The United Kingdom must be linked as closely as possible to European defence

Paradoxically, Brexit has led to renewed British interest in European cooperation in the defence domain.

Prime Minister Theresa May proposed a defence and security treaty with the EU, to define a framework for their future relationship, which would be based on two pillars : an economic partnership, and a security and defence partnership.

In September 2017, the UK Government indicated that it sought a future relationship that would be closer than all existing partnerships with third countries , in other words, a “ deep and special partnership ” with the European Union and its Member States. 58 ( * )

The British government has in particular proposed to contribute directly to CSDP missions. 45 third countries now contribute or have contributed to such missions in the past, whether through specific agreements or under framework agreements entered with the EU. Such framework agreements exist in particular with Norway, Canada, Turkey and the United States. These agreements involve States concerned downstream of decisions made by the EU, however, whereas the United Kingdom seeks involvement as far upstream as possible. It is clear, however, that the UK government will no longer be able to participate in the launch of an operation, as it will no longer be a member of the EU.

The UK government has also expressed interest in Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), including the Military Mobility Project and the European Defence Fund (EDF). It also wishes to conclude an administrative arrangement with the European Defence Agency (EDA). More recently, the UK government has proposed the establishment of consultation and coordination structures. 59 ( * )

The United Kingdom wishes to continue participating in the Galileo programme, including the encrypted part for military use only (Public Regulated Service, or PRS). However, the EU does not want companies from third countries to participate in future calls to tender concerning the encrypted part of Galileo. As for access to Galileo's secure signal as such, European authorities have proposed that the United Kingdom negotiate an agreement to gain access, a proposal that has also been made to the United States. The British government has, for its part, mentioned the possibility of developing its own navigation system, which is perceived in Europe as rather absurd.

Your rapporteurs clearly observed the strong resentment created, on the British side, by the denial of access to tenders for Galileo (PRS). This is an issue that will need to be addressed, in the common interest, during negotiations on the framework for future relations.

British participation in armaments cooperation is in our interest, considering the abilities of their industry, and its links to ours (MBDA). It is therefore necessary for European systems, particularly PESCO and the EDF, to be made as open as possible to the United Kingdom when it is in the interest of the EU and its Member States.

The European Security Council , proposed by the President of the French Republic and the German Chancellor (referred to as the “EU Security Council” in the Meseberg Declaration of June 2018), would seem to be an interesting notion if on the one hand it can help keep the United Kingdom anchored to the European continent, and, on the other, if it help can circumvent the cumbersome procedures of the CFSP/CSDP, in particular the unanimity rule. Nevertheless, it is a format that must remain flexible and must involve all EU countries, so that none will feel that a “multi-speed Europe” is being created.

b) Bilateral structural cooperation for European defence

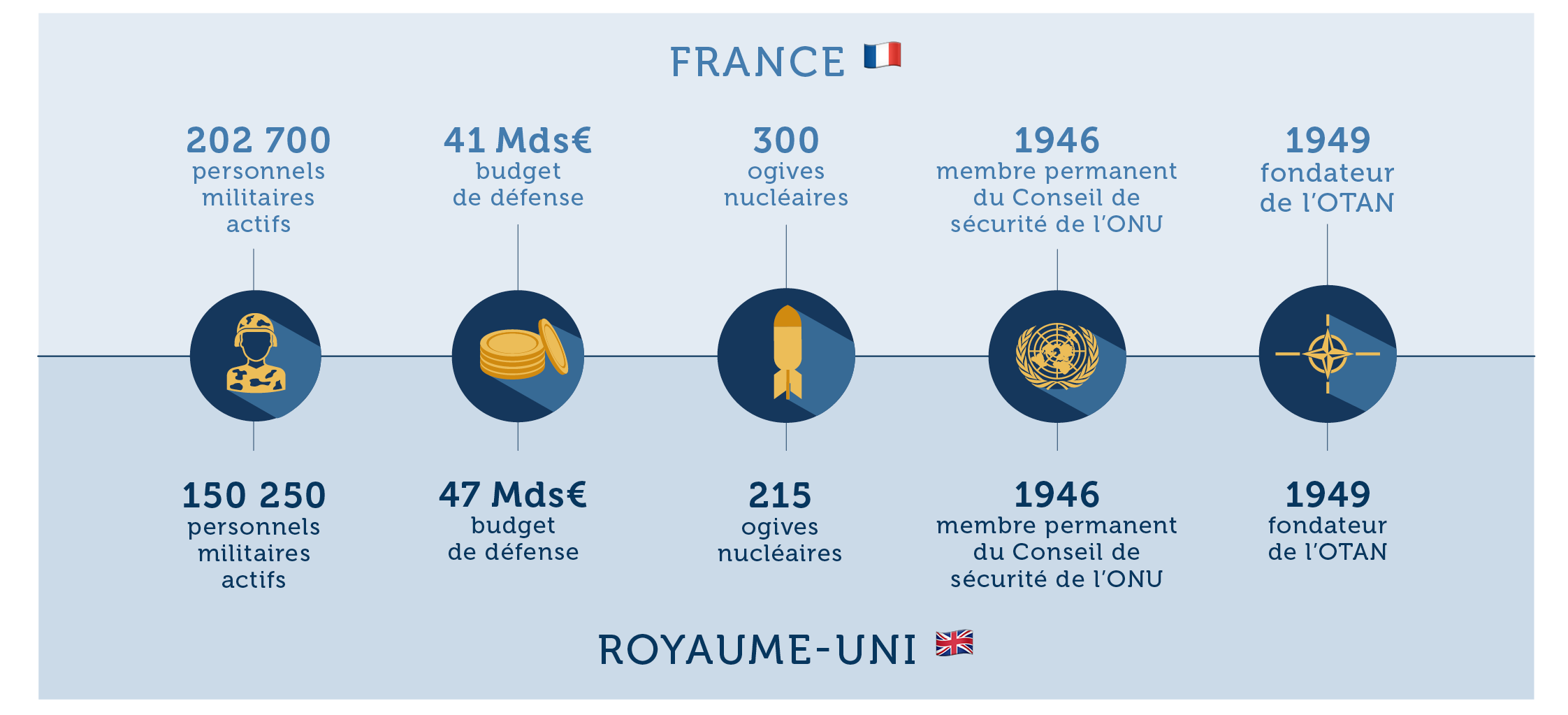

Since the Saint-Malo declaration in 1998, bilateral defence cooperation between France and the United Kingdom has been a defining element of European defence, established between two powers with similar characteristics, whose defence budgets together account for half of all European Union defence spending.

The joint Franco-British operation conducted in Syria alongside American forces in April 2018 illustrated the proximity of our two countries, as did the intervention in Libya in 2011.

Franco-British solidarity was also recently illustrated by the provision of three British “Chinook” CH-47 heavy-lift helicopters at Gao as part of Operation Barkhane.

France and the United Kingdom are also cooperating in Estonia as part of Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP). 60 ( * )

UNITED KINGDOM

FRANCE

150,250 €47 Bn 215 1946 1949

202,700 €41 Bn 300 1946 1949

Permanent membership of UN Security Council

Founding nation of NATO

Nuclear warheads

Defence budget

Active military personnel

Founding nation of NATO

Permanent membership of UN Security Council

Nuclear warheads

Defence budget

Active military personnel

Source: Institut Montaigne 61 ( * )

Franco-British cooperation today takes place in the context of the Lancaster House agreements of 2 November 2010. These agreements establish very close operational and industrial defence cooperation, including a Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF 62 ( * ) ) , which should be declared fully operational by 2020, as well as several major industrial projects. These bilateral agreements will of course continue to apply even in case of a “hard Brexit”.

Cooperation in the missile-manufacturing domain

Maritime Mine Countermeasures Programme (MMCM)

Other programmes carried out jointly

in the European Union context (ex: A400M aircraft)

INDUSTRIAL

NUCLEAR

OPERATIONAL

Establishment of a joint Franco-British commission in 1992

Sharing of installations between the two countries to conduct nuclear test simulations

Sharing of sensitive information for better coordination

Creation of a Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF)

Joint military operations

(in Libya in 2011, with support from the United States)

Proliferation of officer exchange programmes between the two armies

The Lancaster House agreements: the three pillars of Franco-British cooperation

Source: Institut Montaigne

These agreements were reconfirmed in January 2018 at the Sandhurst Franco-British Summit.

On the industrial front, the Lancaster House agreements have made cooperation a priority so as to develop joint weapons programmes and permit economies of scale. MBDA is one of the biggest success stories in this field, involving a high degree of interdependence between our two countries.

The Lancaster House agreements were intended to permit the development of three major joint projects:

- The Future Combat Air System (FCAS): In 2014, BAE Systems and Dassault Aviation were commissioned to perform a feasibility study for this new generation combat system programme. Franco-British cooperation on the project was however suspended in 2017 in favour of Franco-German cooperation, and a few months later, the British announced the launch of their own project (Tempest). Spain has signed on to the FCAS project, but Italy and Sweden, on the other hand, seem more interested in joining the Tempest project.

- The Future Cruise and Anti-Ship Weapon (FC/ASW) programme, being handled by MBDA, intended to supersede the Scalp and Storm Shadow missiles as well as the Exocet and Harpoon anti-ship missiles.

- The MMCM (Maritime Mine Counter Measures) “mine warfare” programme, officially launched in March 2015, which includes the participation of Thales and BAE Systems.

Brexit will not impact our bilateral relationship in the short term. But it could, however, have indirect consequences , linked to a certain “resentment” - a word that came up several times during your rapporteurs' interviews in London. This resentment towards the European Union and towards France in particular would seem to come from the perception that they had taken too inflexible a position in negotiations concerning the content and deadlines for Brexit, and concerning Galileo as well.

To give a renewed momentum to our bilateral relations, it is essential for the exit of the United Kingdom on 31 October (if it does in fact take place on this date) to go smoothly.

Is British participation in the Franco-German combat aircraft programme still possible? This would involve a convergence between the Tempest and FCAS projects; the latter of these two is currently at a more advanced stage. Given the degree of technology required, the cost of these projects - the cost of the FCAS project is estimated at several tens of billions of euros - and the similarity of needs between France and the United Kingdom, it would seem self-evident that it would be preferable to have a joint project rather than competing projects. The opinion shared by all our interviewees is that there is no room for two projects of this type in Europe. Your rapporteurs urge them to reconcile their aims before the ten-year anniversary of the Lancaster House treaty in 2020.

* 54 11 February 2019.

* 55 House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, “Defence Equipment Plan 2018-28”, 23 January 2019.

* 56 Source: NATO

* 57 Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, president of CDU, Olaf Scholz, vice-chancellor and member of SPD, and Wolfgang Schäuble, president of the Bundestag, have made remarks to such effect.

* 58 “A deep and special partnership that will make available UK assets, capabilities and influence to the EU and European partners”, cited by: House of Commons Defence Committee, “The Government's proposals for a future security partnership with the European Union,” 5 June 2018.

* 59 Framework for the UK-EU Security Partnership, Department for exiting the EU (May 2018).

* 60 “ Enhanced Forward Presence” is a defensive and proportionate presence intended as a contribution to strengthening NATO's defence and deterrence posture in the east (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland). Since April 2017, France has had nearly 300 soldiers deployed for this purpose (“Lynx” detachment).

* 61 “Partenariat franco-britannique de défense et de sécurité : améliorer notre coopération”, Institut Montaigne, King's College London, November 2018.

* 62 Combined Joint Expeditionary Force: intended for joint intervention in high intensity operations and early entry into the field (up to 10,000 troops).