III. INITIATIVES NEEDING BETTER OVERALL COHERENCE

In the course of their travels, your rapporteurs have become aware of the dynamism of the bilateral and multilateral (also referred to as “minilateral”) cooperation in place among European nations in the defence field. This dynamism is very positive, but it raises the question of the articulation of initiatives and the overall coherence of European defence.

A. A MULTITUDE OF INITIATIVES THAT DEMONSTRATE THE DYNAMISM OF THE IDEA OF EUROPEAN DEFENSE

Even after six months of work and seven trips around Europe, it would be an illusion to imagine that we might be able to give an exhaustive view of all the cooperative arrangements in place around the continent, because there are just so many of them. Our report will therefore simply give a few examples to illustrate the dynamism of these initiatives, without claiming to be exhaustive.

1. Multiple regional subgroups

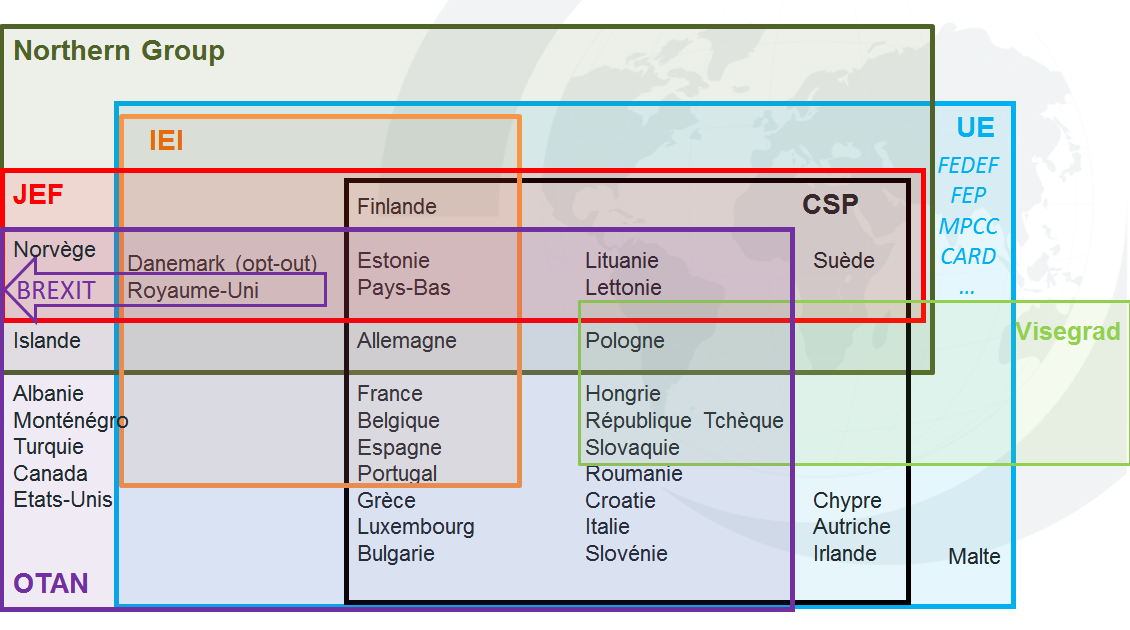

The diagram below illustrates the complexity of the European defence architecture; NATO and the EU are its main pillars, but it includes multiple supporting walls as well.

European defence: a complex architecture

E2I

JEF

NATO

EDF

EPF

MPCC

CARD

etc.

EU

Montenegro

Poland

Czech Republic

Hungary

Portugal

Spain

Belgium

France

Cyprus

Austria

Ireland

Malta

PESCO

Sweden

Lithuania

Latvia

Denmark

Finland

Germany

Greece

Luxembourg

Bulgaria

Slovenia

Italy

Croatia

Romania

Slovakia

United States

Canada

Turkey

Albania

Iceland

Norway

Netherlands

Estonia

United Kingdom

Source: Interview with Alice Guitton and Nicolas Roche

a) Cooperation between neighbouring countries: the example of Romania

We have already mentioned several examples of cooperation between neighbouring countries: bilateral cooperation between France and its European partners, Belgian-Dutch cooperation, and German-Dutch cooperation.

There are many other examples.

Your rapporteurs travelled to Bucharest on the occasion of the Interparliamentary Conference for the CFSP/CSDP, organised by the Romanian Presidency of the European Union.

Romania considers NATO, which it joined in 2004, to be the keystone of its defence policy. Since 2015, it has been home to the command of the Alliance's Multinational Division South-East, as well as to a NATO “Force Integration Unit” (NFIU), and since 2016 has hosted a ballistic missile defence system. At the NATO Summit of 2016, it was resolved that a “Tailored Forward Presence” would be established in South-East Europe, including a multinational brigade in Craiova, bringing together detachments from ten contributing States. Romania has allocated 2% of its GDP to its defence budget since 2017.

Romanians are very concerned about what Russia has been doing in their backyard. Since the nation borders on the Black Sea, which some Romanians fear Russia seeks to turn into an inland sea all of its own, they think of themselves as directly bordering Russia, and have warned us in this context against taking any approach to strategic autonomy that would lead to “strategic isolation.”

Strategic autonomy, they believe, must be a means not to isolate Europe but to strengthen its contribution to NATO.

Romania is engaged in multiple cooperation arrangements with the armed forces of its neighbouring nations:

- A joint Romanian-Hungarian peacekeeping battalion , created in 1999: drawing inspiration from the Franco-German Brigade (FGB, see below), this mixed battalion was established in view of promoting confidence and security between the two armed forces whilst promoting the compatibility and interoperability of their equipment.

- The Multinational Engineer Battalion “TISA , ” created in 2002 by Slovakia, Ukraine and Hungary.

- The Multinational Peace Forces South-Eastern Europe (MPFSEE) and its operational component, the South-Eastern Europe Brigade (SEEBRIG): created in 1998, this organisation includes the participation of Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, Northern Macedonia, Romania and Turkey. Its mission is to conduct peacekeeping operations under the leadership of NATO or the EU, and under the mandate of the UN or the OSCE.

b) A mosaic of initiatives

Outside the EU and NATO, there is a mosaic of plurilateral, variable geometry initiatives that vary enormously in scope. Many of these fall under what is referred to as “minilateralism,” i.e., “cooperation agreements involving between two and ten States, whose basic approach is to involve only a small number of participants and to not require dedicated permanent institutions,” 74 ( * ) or to require only light, non-bureaucratic institutions. This is intended to help avoid the blockages associated with the functioning of multilateralism, which generally speaking has been increasingly questioned.

Minilateralism generally involves the participation of neighbouring States that share the same threat perception and similar strategic cultures.

There are several such sub-regional groups in Europe, some examples of which include the following:

- Northern Group: Initiated by the United Kingdom in 2010, this informal group includes States bordering the North Sea and the Baltic Sea: Northern European States (including Sweden and Finland, non-NATO members), the Baltic States, the Netherlands, Poland, the United Kingdom and Germany.

- NORDEFCO (Nordic Defence Cooperation): created in 2009, NORDEFCO brings together the five Nordic States that are members of the Nordic Council (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden). It includes a political cooperation component and a military cooperation component. This is also a model of “à la carte” cooperation.

- Military cooperation of the Visegrad Group countries, known as the V4 (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovakia), which includes a Battlegroup (EUBG); the Central European countries are also cooperating in their Central European Defence initiative. 75 ( * )

EU battlegroups are an attempt to federate a wide variety of initiatives. They do at least have this merit, even if they have still never been deployed to date, and are generally considered an EU failure.

2. What rapid reaction force for Europe?

a) Multiple attempts

Among the various multinational initiatives being conducted in Europe, many have the same still-unfulfilled goal: the creation of a rapid reaction force capable of intervening urgently to help maintain or restore peace in the event of a crisis outside EU territory, in place of the ad hoc coalitions that generally play this role.

Europe is casting about in pursuit of a joint reaction capacity , which would clearly be a decisive milestone on the path towards European defence.

Among these attempts, the establishment of the EU Battlegroups (EUBG) , previously mentioned in this report is emblematic of the difficulties that have been encountered. They have never been deployed to date because of a lack of political agreement, but have allowed a wide range of multinational contacts to be made that may in time prove fruitful.

We should also mention here the NATO Response Force (NRF) , a joint multinational force created in 2002, which the NATO nations decided to strengthen in 2014, creating within it a “Very High Readiness Joint Task Force” (VJTF), commanded by Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). The EUBGs and the NRF are made up of units assigned to them from the armed forces of the participating countries, which rotate every six months to ensure permanent readiness. NATO is also implementing a new “Readiness Initiative” (NRI), in which France will be a major participant; its intention is to ensure that in 2020 the allies will have 30 mechanised battalions, 30 air squadrons and 30 battleships ready to use within 30 days or less (an initiative known as 4x30).

Here of course we must mention the existence of the Eurocorps, which historically was one of the first attempts to have a European rapid reaction corps , as its creation dates back to 1992, at the initiative of France and of Germany. Comprising 5 Member States (France, Germany, Spain, Belgium, Luxembourg), the Eurocorps is a military staff corps based in Strasbourg, which is intended to command forces engaged in EU or NATO operations. It is able to command up to 60,000 troops, and participates in duty rotations both in the EUBGs and the NRF. This European Corps has participated in NATO operations in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Afghanistan, as well as in the framework of EU missions in Mali and the Central African Republic.

Several multinational forces have also been established, with the aim of providing a swift crisis-response:

- The Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF): Created in 2014 under the impetus of the United Kingdom, this force brings together several northern European countries: United Kingdom, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands and the three Baltic States. It was declared fully operational in 2018 and will be conducting exercises in the Baltic Sea this year (Baltic protector).

- The Combined Joint Expeditionary Force (CJEF): A Franco-British corps created under the Lancaster House agreements (see above) and comprising 5,000 personnel, the CJEF has the advantage of involving the two largest European military powers, which have similar strategic cultures. It is slated to be declared fully operational by 2020.

- The Franco-German Brigade (FGB): created in 1989, the FGB is a binational unit composed of 5,600 soldiers, 40% of whom are French and 60% German, stationed on both sides of the Rhine, including a staff, six regiments and battalions and one commando company. The FGB intervened as part of the Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina (SFOR), Afghanistan (ISAF) and Kosovo (KFOR). In 2018, the FGB was deployed in Mali: the French section as part of Operation Barkhane, and the German section as part of MINUSMA and EUTM-Mali; this illustrated the difficulties of implementing a multinational force without unifying the cultures and rules of engagement - or in other words, ultimately without political unification.

Such is the question that the European Intervention Initiative (E2I), created in order to bridge strategic cultures, seeks to answer.

b) The European Intervention Initiative

Announced by the President of the Republic during his speech at the Sorbonne on 26 September 2017 and officially launched on 25 June 2018, the European Intervention Initiative (E2I) is a recent illustration of the spirit of minilateralism.

Its aim is to foster the emergence of a European strategic culture, so as to strengthen the capacity of the 10 participating States 76 ( * ) to act together to address the full spectrum of crises in the context of jointly organised and coordinated engagements.

The organisation is of a deliberately informal nature, holding regular meetings at several levels, but never establishing itself as an institution. It works to help reinforce NATO and the EU - although it is independent from those two institutions - first of all by improving the capacity of its members to conduct joint military activities, and second by facilitating the emergence of concrete projects, particularly in the framework of Permanent Structured Cooperation. The E2I is also a welcome development in that it allows inclusion of the UK, in spite of Brexit, and of Denmark, in spite of its opt-out from the CSDP.

Your rapporteurs are of the opinion that it is our vital responsibility to work to reconcile strategic cultures, including at the parliamentary level, by multiplying our contacts with all our European partners. They have endeavoured to initiate that approach as part of this report. To give a parliamentary dimension to the E2I , in a flexible, informal context, might be a way to help generalise this approach (all participating countries could be invited) and make it more consistent.

In order to get more countries involved, such as Italy, Poland and other non-member countries of Northern and Eastern Europe, this dialogue amongst national parliaments on military and strategic issues could also be held as part of a European Defence Summer School.

3. Two examples of pooling resources

Two successful examples of the pooling and sharing of resources should be mentioned here: EATC and Helios/Musis. These are operational cooperation arrangements, undertaken with a view to efficiency in rationalising the use of European assets, in the field of military air transport for the one and of space-based observation for the other.

a) Sharing of air transport resources

The EATC ( European Air Transport Command), the objective of which is to optimise the use of military air transport resources to generate cost synergies, is a successful example of resource sharing . Pooling the capabilities of multiple countries provides multiple benefits, apart from the obvious synergies. It makes it possible, for example, to choose the most appropriate aircraft to obtain the overflight authorisations required for a given mission, in light of the special relationships that may be in place between countries.

Established in 2010 and based in Eindhoven (Netherlands), the EATC is a unique organisation, bringing together 7 countries (Germany, Belgium, France and the Netherlands since the beginning, Luxembourg since 2012, and Spain and Italy since 2014). The seven member countries manage their military air transport resources under a single command. The fleet is made up of more than 170 aircraft stationed at 13 national air bases, representing 60% of Europe's military air transport capacity. The EATC also conducts air refuelling and medical evacuation missions. States are free to refrain from sharing their full capabilities.

The EATC is in particular to manage the 8 A330 MRTT aircraft of the MMF ( Multinational Multi-Role Tanker Transport Fleet ) project, which brings together 5 countries (Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway). These aircraft will be operated by the multinational MRTT unit (MMU) and will be co-located at the Eindhoven and Cologne air bases. The capacity portfolio of the EATC will thus be supplied by a multinational force, the MMF project being itself a model for cooperation arrangements within Europe. The flexibility of the arrangement also permits a State that is not an EATC member (Norway) to participate in it anyway, via the support of a participating country.

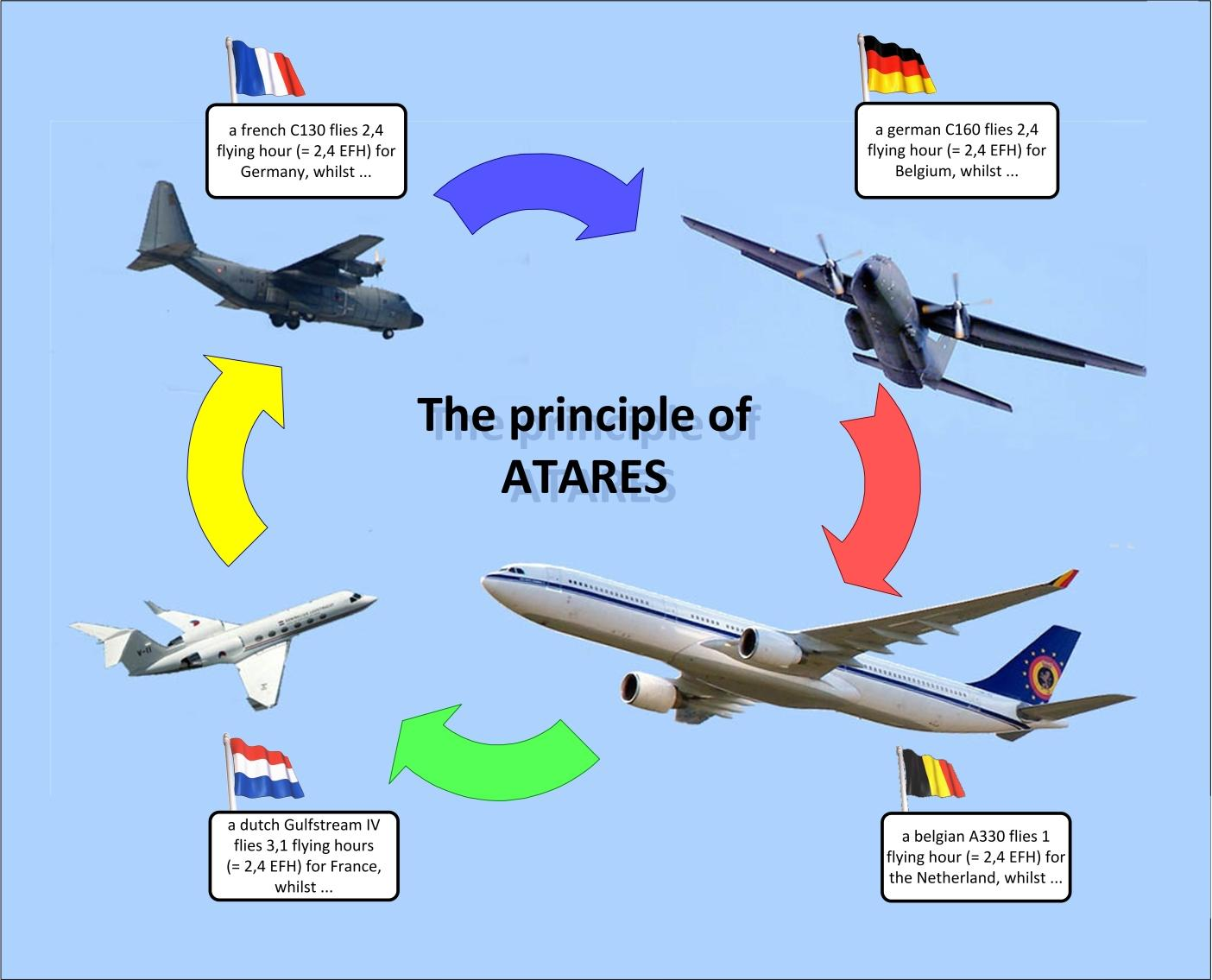

Exchange of services within the EATC is conducted according to the principles of the ATARES arrangement. 77 ( * ) This exchange is based on the notion of Equivalent Flying Hours (EFH) for each national asset. The reference is the cost price of one C-130/C-160 flying hour (EFH=1). Participating countries are expected to provide the ATARES community with as many EFHs as they receive. Thus, under ATARES, for example, a French C130 may fly for Germany (2.4 hours), a German C160 may fly for Belgium (2.4 hours), a Belgian A330 may fly for the Netherlands (1 hour), which may provide a Gulfstream IV to France (3.1 hours). The respective durations on each aircraft represent equivalent entitlements to service.

Source: EATC

Thanks to the replacement of the European transport fleets (A400M, A330 MRTT), the EATC will play a key role in making Europe more autonomous and more responsive in the military air transport domain.

The EATC is a successful example of a directly operational cooperation arrangement established outside the multilateral institutional frameworks. Its success lies in its flexibility, with each State remaining sovereign and entitled to withdraw the assets it shares. This is an unfamiliar example of the success of European defence, which should be replicated in other domains, such as the pooling and sharing of helicopters or medical support resources.

b) Satellite intelligence sharing

Satellite intelligence sharing is clearly in the interest of all European partners. It should also help prevent duplication of capacities.

With its Helios, Pleiades and, soon, Musis-CSO (Optical Space Component) systems, France has space-based optical intelligence capabilities unparalleled in Europe. Agreements signed with Italy (2001) and Germany (2002) allow programming rights to be exchanged between Helios 2 and the COSMO-Skymed (Italy) and SAR-Lupe (Germany) radar systems.

The Helios programme now has five partners: France, Belgium, Spain, Greece and Italy.

General Michel Friedling, Commander of the Joint Space Command, gave an update on this issue during a hearing with your Committee on 13 February 2019:

“In the observation domain, we currently have in service the HELIOS 2 satellites, the twofold constellation PLEIADE, and access to the German SAR-LUPE and COSMO-SkyMed radar services. In the listening domain, the experimental low-orbit satellite constellation ELISA provides our primary capacity, and in the communications domain, the SYRACUSE 3 satellites comprise our sovereign core, supplemented by the Franco-Italian satellite ATHENA-FIDUS, famous for being “poked into” by a Russian satellite in 2017, as well as the services offered by the Italian government satellite SICRAL 2 and under the commercial contract ASTEL-S. Space has never been left out of the military planning law (LPM); indeed, the law devotes €3.6 billion to the full renewal of our military space capabilities over the next seven years: HELIOS 2 will thus be replaced by the MUSIS-CSO programme, whose first satellite was launched last December.”

It is nevertheless regrettable that European cooperation in the satellite field is being disrupted by German efforts to build its own optical observation satellites , with an order having been placed with the German manufacturer OHB for such purpose in 2017.

In addition, the European Union Satellite Centre (EUSC) , based in Torrejon de Ardoz, Spain, provides significant support to the CSDP. It supplies products and services based on the use of space assets and collateral data, particularly satellite and aerial imagery, as well as related services.

* 74 Le « minilatéralisme » : une nouvelle forme de coopération de défense, Alice Pannier, Politique étrangère 1:2015.

* 75 Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Slovenia.

* 76 Germany, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Estonia, France, Finland, the Netherlands, Portugal and the United Kingdom.

* 77 Air Transport & Air to Air Refuelling and other Exchange of Services