Rapport d'information n° 626 (2018-2019) de M. Ronan LE GLEUT et Mme Hélène CONWAY-MOURET , fait au nom de la commission des affaires étrangères, de la défense et des forces armées, déposé le 3 juillet 2019

Disponible au format PDF (2,2 Moctets)

-

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

-

FOREWORD

-

PART ONE - THE EUROPEAN UNION AS THE SECOND PILLAR

OF EUROPEAN DEFENCE: A HISTORIC TURNING POINT TO ENSURE THE SECURITY OF

EUROPEAN CITIZENS

-

I. EUROPEAN COUNTRIES PROVIDING FOR THEIR OWN

DEFENCE: A NECESSARY AMBITION

-

A. A REALITY: THE UNITED STATES STILL PLAYS A

PREPONDERANT ROLE IN THE DEFENCE OF THE EUROPEAN CONTINENT

-

B. “SHARING THE BURDEN”: A NECESSITY

FOR EUROPEANS

-

A. A REALITY: THE UNITED STATES STILL PLAYS A

PREPONDERANT ROLE IN THE DEFENCE OF THE EUROPEAN CONTINENT

-

II. THE EU AS A MAJOR STAKEHOLDER IN EUROPEAN

DEFENCE: THE NEXT STEP NOW BEING TAKEN

-

A. THE EMERGENCE OF THE EU AS A MAJOR STAKEHOLDER

IN EUROPEAN DEFENCE

-

B. THE EUROPEAN DEFENSE FUND: A MAJOR TURNING POINT

THAT REMAINS TO BE CONFIRMED

-

A. THE EMERGENCE OF THE EU AS A MAJOR STAKEHOLDER

IN EUROPEAN DEFENCE

-

I. EUROPEAN COUNTRIES PROVIDING FOR THEIR OWN

DEFENCE: A NECESSARY AMBITION

-

PART TWO - FAR FROM THE UTOPIAN GOAL OF A

“EUROPEAN ARMY”: A DYNAMIC THAT MUST REMAIN FLEXIBLE AND

PRAGMATIC

-

I. TWO MAJOR PARTNERS: THE UNITED KINGDOM AND

GERMANY

-

A. INTEGRATING THE UK, A VITAL PARTNER

-

B. GERMANY: AN INDISPENSABLE PARTNER

-

1. Germany and defence, a complex issue

-

2. Germany's natural role in European

defence

-

3. The imperative to overcome the difficulties of

implementing a Franco-German partnership

-

a) The strong symbols of Franco-German

friendship

-

b) A context transformed by Brexit

-

c) A partnership relaunched around major

capabilities projects: FCAS and MGCS

-

(1) The Future Air Combat System (FCAS), a

foundational project

-

(2) The other component of the comprehensive

agreement: the future ground combat system (MGCS)

-

d) Implementation difficulties

-

e) Is it possible to reconcile the French and

German conceptions of defence?

-

a) The strong symbols of Franco-German

friendship

-

1. Germany and defence, a complex issue

-

A. INTEGRATING THE UK, A VITAL PARTNER

-

II. MAJOR STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS TO BE

DEVELOPED

-

III. INITIATIVES NEEDING BETTER OVERALL COHERENCE

-

I. TWO MAJOR PARTNERS: THE UNITED KINGDOM AND

GERMANY

-

GENERAL CONCLUSION

-

EXAMINATION IN COMMITTEE

-

LIST OF PERSONS HEARD

-

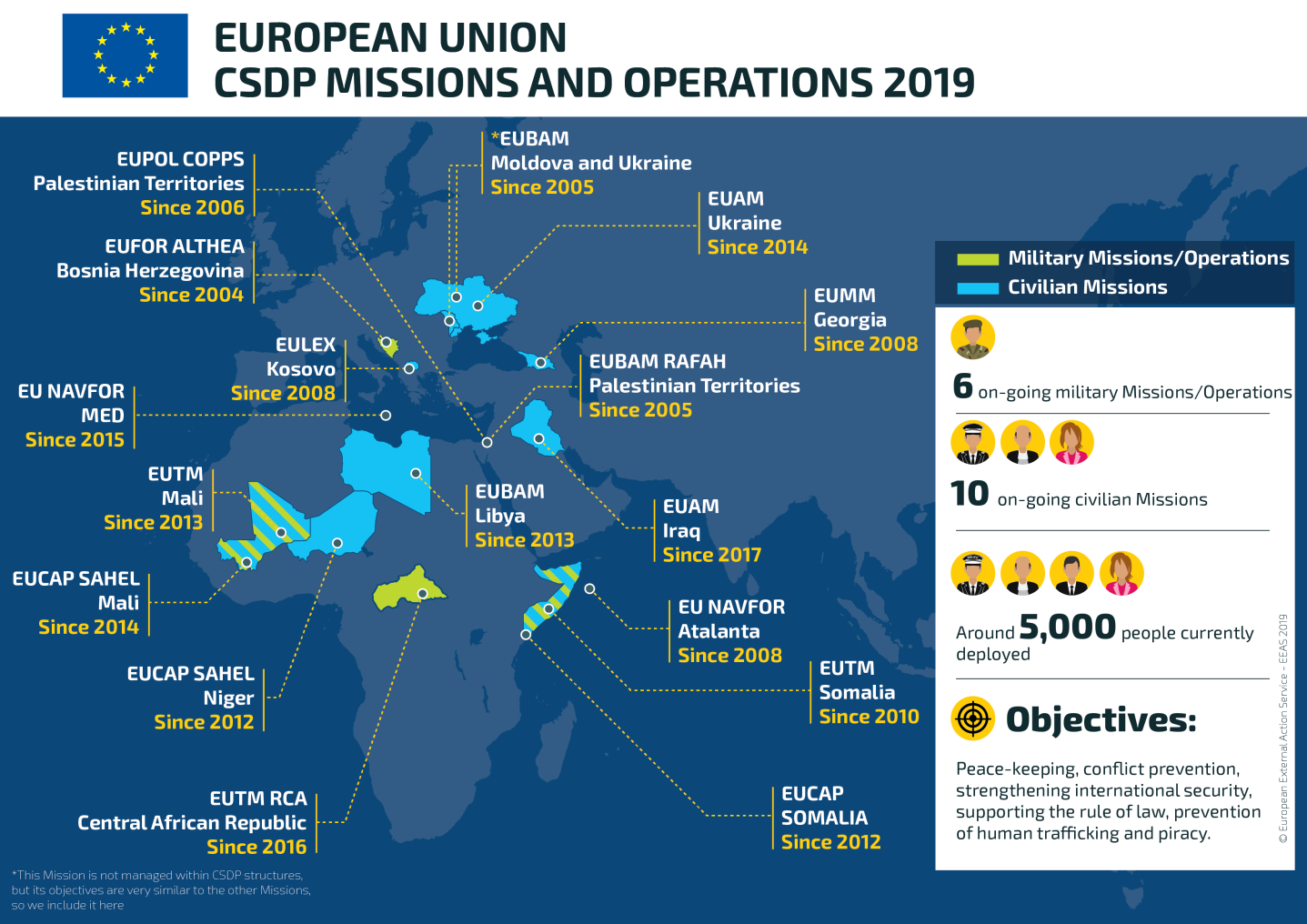

ANNEX 1 -

CSDP MISSIONS AND OPERATIONS

-

ANNEX 3 -

COMMITMENTS OF STATES PARTICIPATING IN PESCO

-

ANNEX 4 - IMPORTANT ACRONYMS

No. 626

SENATE

EXTRAORDINARY SESSION OF 2018-2019

|

Filed at the President's Office of the Senate on 3 July 2019 |

INFORMATION REPORT

DRAWN UP

on behalf of the Foreign Affairs, Defence and Armed Forces Committee (1) by the Working Group on European Defence ,

By Mr Ronan LE GLEUT and Ms Hélène CONWAY-MOURET,

Senators

|

(1) This committee is composed of: Christian Cambon, Chairman ; Pascal Allizard, Bernard Cazeau, Robert del Picchia, Sylvie Goy-Chavent, Jean-Noël Guérini, Joël Guerriau, Pierre Laurent, Cédric Perrin, Gilbert Roger, Jean-Marc Todeschini, Deputy Chairpersons ; Olivier Cigolotti, Joëlle Garriaud-Maylam, Philippe Paul, Marie-Françoise Perol-Dumont, Secretaries ; Jean-Marie Bockel, Gilbert Bouchet, Michel Boutant, Olivier Cadic, Alain Cazabonne, Pierre Charon, Hélène Conway-Mouret, Édouard Courtial, René Danesi, Gilbert-Luc Devinaz, Jean-Paul Émorine, Bernard Fournier, Jean-Pierre Grand, Claude Haut, Gisèle Jourda, Jean-Louis Lagourgue, Robert Laufoaulu, Ronan Le Gleut, Jacques Le Nay, Rachel Mazuir, François Patriat, Gérard Poadja, Ladislas Poniatowski, Mmes Christine Prunaud, Isabelle Raimond-Pavero, Stéphane Ravier, Hugues Saury, Bruno Sido, Rachid Temal, Raymond Vall, André Vallini, Yannick Vaugrenard, Jean-Pierre Vial, and Richard Yung . |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

All European countries wish to preserve peace, that common good of European construction, and we must therefore not miss the historic opportunity for Europe to strengthen its defence due to mistakes, misunderstandings or disagreements that cause us to fall short in addressing the challenges.

After six months of work, dozens of hearings and visits to seven European countries, 1 ( * ) we have noted that the building of European defence is clearly underway, although not in the shape of a formal master plan, and much less of a "European army," but rather in the form of a series of progressive, cumulative and multifaceted developments. The conclusions of this report are the result of careful attention to the analyses and needs expressed by our partners.

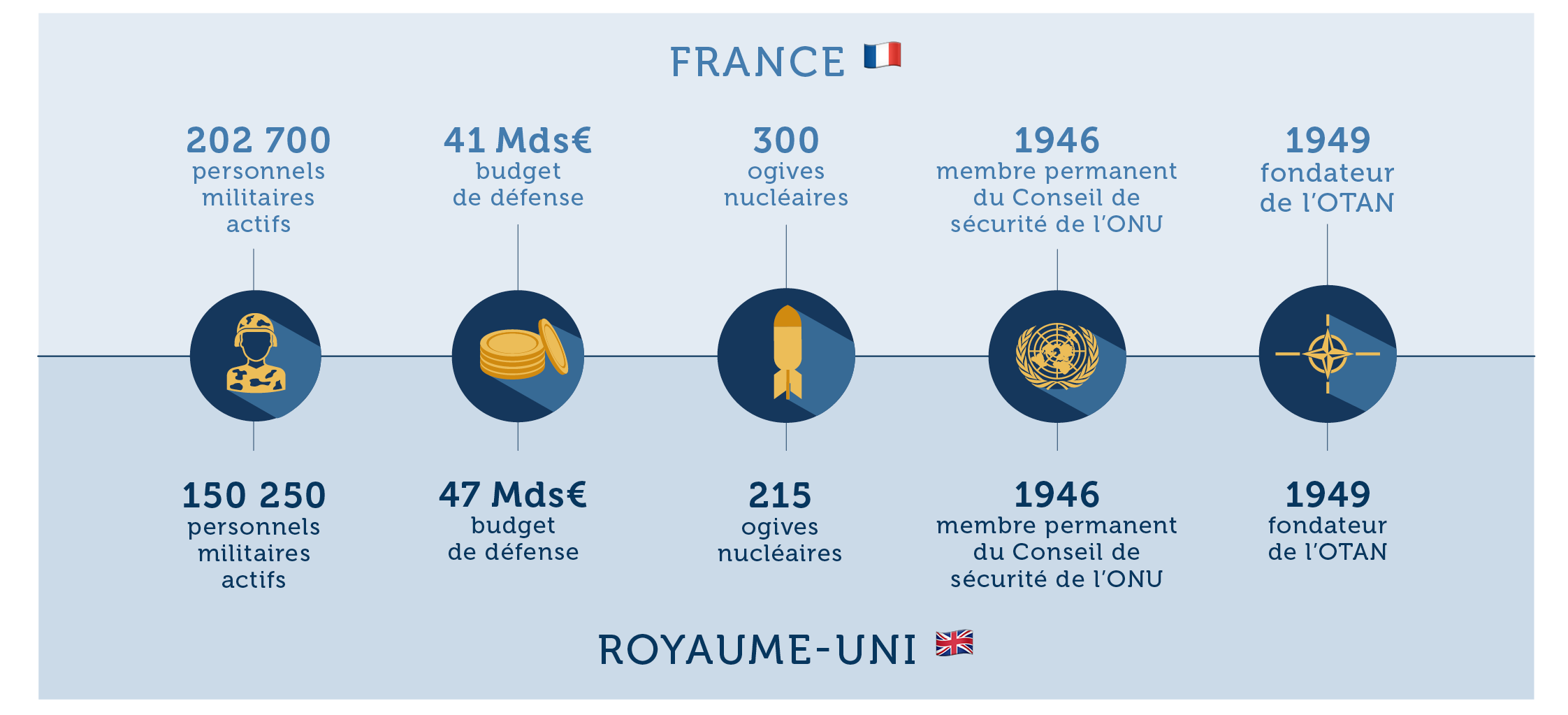

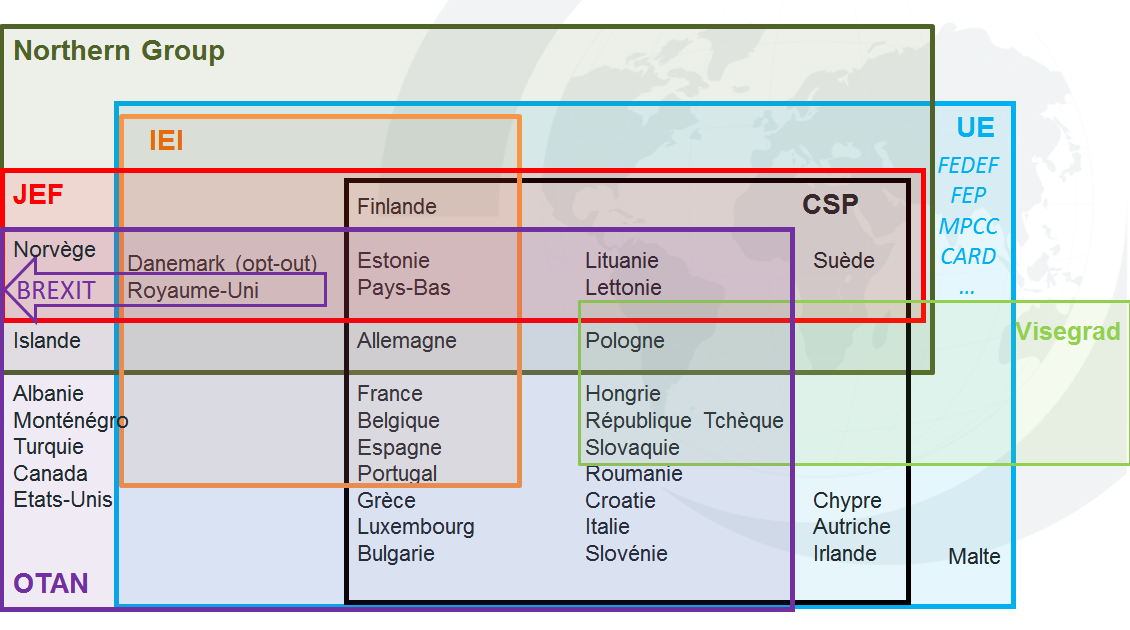

Today, European defence rests on two pillars: NATO and the EU. But it needs the support of public opinion in order to construct it before a major crisis forces our hand:

1. With the notable exception of France and the United Kingdom, Europe has given up on providing for its own defence in recent decades. Since the end of the Cold War, this defence has been provided mainly by NATO, and therefore by the United States, whose expenditure devoted specifically to the defence of Europe is estimated at $35.8 billion, which is slightly less than the defence budget of France . These expenditures finance, in particular, the presence of 68,000 personnel from the five branches of the US military. The United States plays a major role in terms of NATO's strategic and tactical nuclear capabilities.

France plays a key role in defence issues within the European Union. It is imperative for it to strengthen its involvement in NATO, which it re-joined in 2009, with the exception of the Nuclear Planning Group. Since that decision, the post of Supreme Allied Commander Transformation (SACT) has been held by a French general. France is in a key position within NATO to help balance approaches. It is increasingly listened to at NATO, where it has gained credibility because of its participation in Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP), but also by its proven operational competence in external operations (OPEX). It is therefore in a good position to advocate for the strengthening of European defence, not against the United States but with it. Everyone on both sides of the Atlantic can understand that this involves a process of strategic empowerment and a rebalancing of relationships.

But we must also be firm: the defence of Europe cannot be bought with equipment contracts ; that would be contrary to the values ??that have underpinned the exceptional nature of the transatlantic relationship for two centuries. Euro-American solidarity must be unconditional, because its aim is to defend a set of values, our civilisation. Preserving and strengthening the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB) is an essential part of the empowerment process.

2. The terms “strategic autonomy” or “European army” should not be used lightly: these terms are of concern to our partners , because they provoke a fear that the protection of NATO that is considered to be effective might be progressively replaced by a system that is still not clearly defined, and the fear that American disengagement in a virtual sense may end up leading to American disengagement in a real sense. Many misunderstandings with our European partners also arise from linguistic and semantic differences : we tend to use expressions that are ambiguous or not easily translatable, to which each assigns a different significance. France has long spoken of a " Europe de la défense " [a Europe of defence] - an untranslatable expression that should be replaced by the notion of "European defence," which is also closer to what the majority of the European countries want.

We must work to strengthen our mutual understanding, so as to create the conditions for increased interdependence; such is the price that we must all share to build European defence. That good faith will also come about through long-term compliance with established commitments.

3. European opinion today basically breaks down into three groups: Europeans concerned about the threat from the east of Europe (Russia), those who are more concerned about instability originating in the south (Africa and the Middle East), and lastly - and this is probably the case for a significant part of public opinion - those who do not feel concerned by any threat at all. It is urgent that we overcome these divisions and generate a shift in public opinion. It is up to European governments to inform the public about the European Union's achievements in the security and defence field, to explain the security-defence continuum, to highlight Europe's strengths rather than always focusing on its weaknesses, and strive to make advances in European defence before we are forced to do so by a major crisis that would make us realise, only all too late, how serious these issues really are.

12 core proposals:

1. Reinforce the commitments of each country and forge the elements of a European defence based on existing initiatives, work must be done for the collective drafting of a European White Paper on Defence , a link that is currently missing in the chain between the EU's Global Strategy, capacity processes, and existing operational mechanisms.

2. Create the conditions to raise the profile of defence issues within the European institutions : a Directorate-General for Defence and Space, or the creation of a post of European Commissioner or Deputy to the High Representative in these domains, and recognition of a “Defence” format of the Council (which currently handles defence issues in its “Foreign Affairs” format).

3. Multiply exchanges and training systems as well as joint military exercises on a Europe-wide basis, as is essential to building a shared strategic culture: at the military level, France should participate in the Erasmus military system, and create a European session on a basis provided by the Institute of Advanced Studies in National Defence (IHEDN) to develop a common strategic vision for future decision-makers . Gradually increase the admissions capacity at the écoles de guerre (war colleges) to facilitate the joint training of officers. On the political front, step up our contact with our European partners, for example by setting up a European Defence Summer School , which should provide a forum for reflection and parliamentary exchange.

4. As a result of Brexit, create a new position at NATO of Deputy Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR ), which will be assigned to a representative of an EU Member State (in addition to the existing post, traditionally held by a representative of the UK).

5. Better articulate European capacity planning processes, rendering them cyclical and consistent with the long-established, structured process of NATO.

6. Relaunch the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) by concentrating resources where the European Union can provide the greatest added value, as is the case in Africa thanks to the EU's “global approach , ” combining a military component with diplomatic, economic and development assistance components. Expand the resources allocated to the recently created Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC).

7. Defend the budget proposed for the European Defence Fund (EDF) in the next multiannual financial framework 2021-2027, i.e. €13 billion. These credits will need to be granted to projects of excellence chosen for their contribution to European strategic autonomy and the consolidation of the EDTIB, and not allocated in small amounts to a variety of recipients in view of promoting cohesion. Ensure that the EDF serves only the industrial interests of Europe. Plan a project specifically focused on Artificial Intelligence , a crosscutting concern that may also involve States with few or no defence industries.

8. Act to the extent possible to ensure that Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) is an approach capable of filling the capability gaps of the European Union, consistent with the White Paper proposed above, and reaffirm the binding nature of the commitments made by States in that framework , particularly with regard to their procurement strategies , which must be favourable to the development of the EDTIB.

9. Clarify the functioning of Article 42 (7) of the Treaty on European Union by assigning an informational and coordinating role to a specific EU body, for example the High Representative. Conduct an upstream analysis of the possibilities for the activation of this article, as well as the procedures for providing the assistance requested (in consideration of the lessons learned from France's activation of the article in 2015).

10. Propose as a top priority for the EU the establishment of a defence and security treaty with the UK, as a vital partner of European defence to which we must offer flexible solutions to enable it to participate as much as possible in EU systems (EDF, PESCO, Galileo, etc.).

11. Major Franco-German industrial projects are key elements in the future of European defence. But for those projects to succeed, we must be frank and candid in our discussions with our German partner , because unless we have a clear agreement on export rules and maintain a balanced industrial distribution in the long term - in other words, unless legal and economic security is ensured - these projects will not be able to continue. These projects must serve as a starting point to allow other European partners to join in and help build a veritable European consortium.

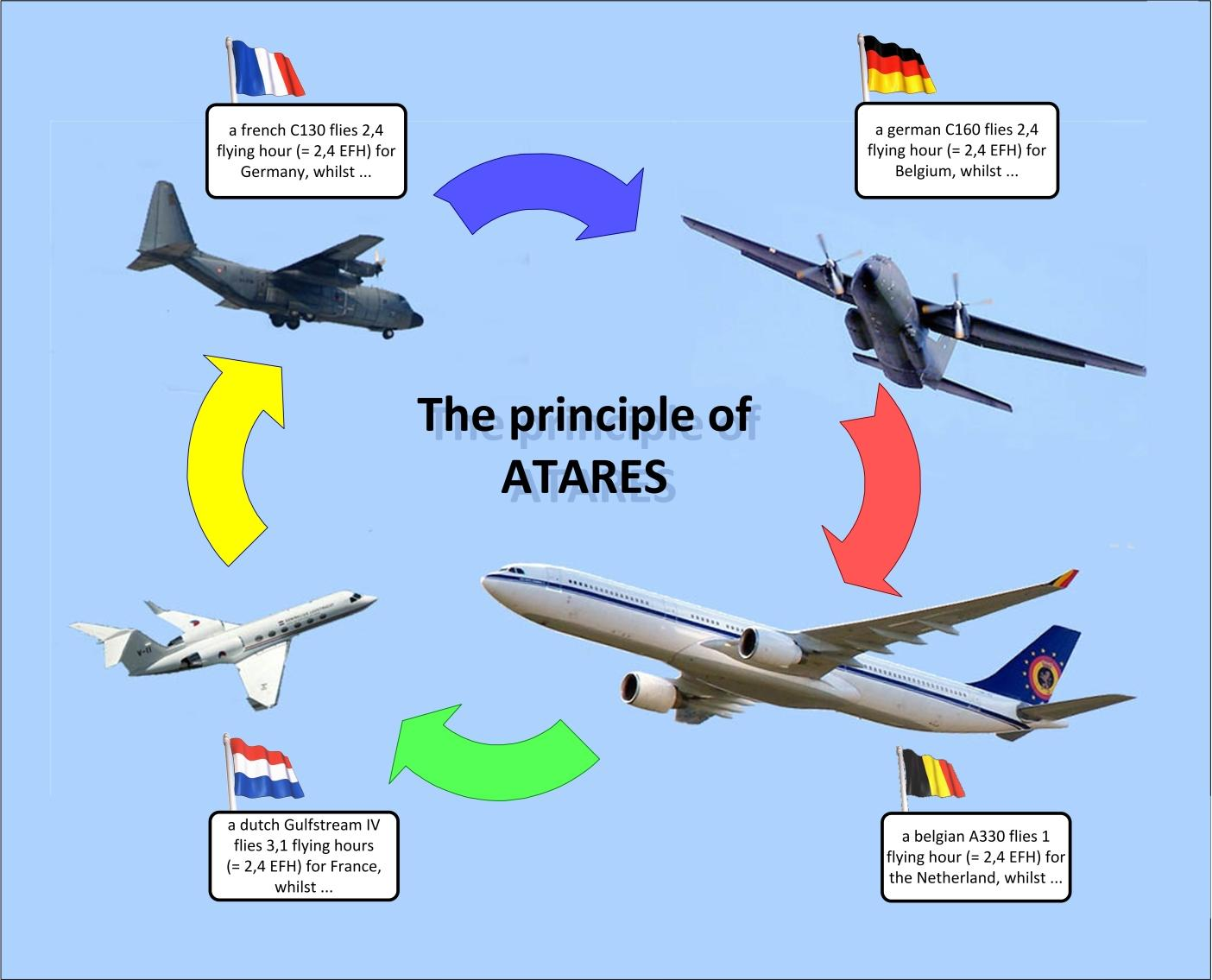

12. Preference and encouragement should be given to flexible mechanisms , both inside and outside the EU, i.e., spontaneous cooperation or pooling mechanisms , similar to those established with regard to military air transport (EATC), whose underlying principle should be extended to other areas (helicopters and medical support, for example).

FOREWORD

?ôé ôïß ðïôå ê?íôßïò ?óó?

“Truly a day will come when you will have to face the foe.”

Herodotus, Histories, VII, 141

European defence is like the proverbial glass: some say the glass is half empty; others say it is half full. The work conducted by your rapporteurs these past six months has inevitably brought them to the side of the optimists, those who see the glass half-full and filling. Faced with the erosion of multilateralism and the increasingly uninhibited attitudes of the great powers, Europe is in a difficult position in terms of its defence. And yet, at no time since the Second World War has it held such a good hand.

With the notable exceptions of France and the United Kingdom, each of which ultimately developed nuclear weapons, Europe gave up on providing for its own defence in the second half of the twentieth century. This was due on the one hand to the political, material and moral weakening caused by the two World Wars, and on the other to the fact that starting in 1945, the continent became a space that was disputed between the United States and the USSR in the Cold War.

In spite of this very specific context, the question of Europe's security has remained central. In particular, it was one of the reasons behind European integration, born out of the resolve of the six founding countries to make any new war between them impossible. This goal has been brilliantly achieved. Other threats have emerged or become stronger, however. The question of European defence is thus hardly a new one. It has been and will remain an objective for the future, shared among the peoples of Europe, whether their governments make it a priority or not. From this perspective, it is likely that in the future when we look back on history we will see the end of this decade as a turning point in the process of European construction.

More than any other, the defence field is characterised by its ties with national sovereignty, thus making it deeply political, but this political nature is not shaped by the domestic agendas of the leaders of the European countries: it is above all the result of geopolitical pressures, pressures over which those who govern our democracies for a limited period of time have little control.

As your rapporteurs conducted their work over these six months, the ambivalence of the pressures weighing upon Europe have appeared clearly to them: on the one hand, Europe finds itself facing its responsibilities as the non- European powers become increasingly uninhibited in their actions; on the other, the difficulty of the situation requires it ever more urgently to rouse itself from its inaction as a geopolitical entity. Otherwise, it will soon fall into a kind of vassalage, which, informed by the work they have now completed, your rapporteurs do not believe to be really accepted in any of the European countries.

The spotlight constantly cast upon the tensions and divergences between the European governments obscures the significant collective convergence of ideas amongst Europeans on some fundamental issues. It also fails to take into consideration both the shared destiny that unites us and the awareness of that shared destiny among the various European peoples.

The subject of European defence has been the focus of many reports, conferences, and a variety of studies, many of which are of very high quality. The aim of this report is not to provide a synthesis of these works, but to situate the French perspective in the wider European context, which, while it is very well known and has been abundantly described by specialists on the issue, has been largely ignored in our domestic debates. It would certainly be an unusual approach to simply assert a vision of European defence without looking into what our European partners might think. Yet this is precisely what we have been doing for quite some time now. It might have been understandable back in the 1960s, when France was seeking to set itself apart from its partners, but today, how can we think of building European defence without listening to and trying to understand the points of view of other European countries?

In this respect, the situation is very clear. For all of our European partners, and most French specialists as well, it is an obvious fact that the defence of Europe today is provided essentially by NATO, which is to say, in more concrete terms, by the United States of America. 2 ( * ) Nevertheless, France has expressed its vision in a way that has sometimes led our partners to perceive it as harbouring a desire to disengage from the United States. Clearly, the fact that our position is perceived in this way casts confusion over what we are saying about the necessity of strategic autonomy for Europe. The difficulty we have had in hearing and understanding our partners' points of view has weakened the credibility of our proposals and, to put it simply, harmed our interests.

France is right in asserting that in the face of rising threats, Europe will need to be able to defend itself, protect its interests, and protect its citizens. But all the other European countries are also right to observe that in the short term, Europe is unable to defend itself without the help of the United States. Denying this obvious state of affairs, as we sometimes appear to be doing when we suddenly introduce certain poorly-defined concepts into the debate, inspires incomprehension or even concern among our partners. In the discussions your rapporteurs have held with their foreign contacts, however, the convergences largely outweigh the differences. We are therefore often wasting precious time and energy attempting to explain, justify and defend our positions, when these positions ultimately are not unacceptable to our partners.

This report aims to show how, through a host of initiatives of all kinds (political, institutional, industrial, operational, etc.), the European countries have now entered a new phase, which is possible only because there is in fact a rising global awareness that the international context has changed.

The first major element of this change is the growing tension between the United States and China. Seeing China as its main strategic competitor, and Southeast Asia as its main focus, the United States has made it quite clear that Europe, in contrast, is not its strategic priority. As was emphasised several times in the hearings conducted by your rapporteurs, this new course predates the election of Donald Trump as the President of the USA. Rather, it was Barack Obama who was the first to define this “strategic pivot”, and while this vision may have been expressed more vigorously under President Trump, the fact is that two successive presidents from two different political parties have now shared it, which obliges us to consider it as a permanent change. Even our European partners who are most committed to the transatlantic bond are aware of this, but they also point out that Europe is unable to defend itself without the United States for the time being, and thus conclude that it is essential to avoid doing anything that might weaken that American protection.

The second element in this context is the interventionist attitude of Russia. This was initiated with the Russo-Georgian war of 2008 and has inched closer to European territory with the intervention in Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea in 2014. But the renewed use of Russian force also manifested itself in Syria, where Russia rescued the regime of Bashar al-Assad, which was about to be overthrown. This new posture has now been displayed around all the borders of Europe through an air and naval presence that is akin to a constant show of force. Added to this have been its disinformation, cyber-attack and espionage activities, whether for intelligence purposes or for violent ends, such as the murder attempt on dissident Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom. This conduct on Russia's part has reinforced the conviction of many European countries that the threat on Europe's Eastern flank makes a continued American presence essential. These same countries consider that the primary strategic objective of Russia is to detach the United States from the European continent so that it can then have free rein. This prospect explains the concerns felt in these countries when there are episodes of tension between Europeans and Americans.

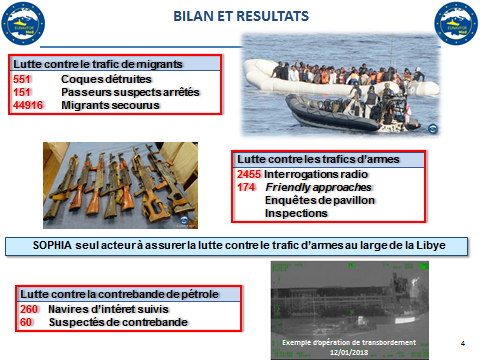

The third contextual element is the development of threats on the Southern front. These are of two kinds. On the one hand, European countries have in recent years experienced a series of unprecedented jihadist terrorist attacks. On the other, the civil war in Iraq and Syria, aggravated by the emergence of the caliphate of the Islamic State (IS), has generated a considerable flow of migrants towards Europe. Likewise, the collapse of the Libyan State following the Western intervention there has facilitated the establishment of criminal networks focused on Europe, profiting in particular from human trafficking and the exploitation of migrants trying to enter Europe. Finally, the weakening of the States in the Sahel-Saharan Strip (SSS) has made that area a base for jihadist networks and organised crime, with the two sometimes overlapping.

However, if the terror attacks that have hit France since 2015 have taught us anything, it is that the situation in the Near and Middle East and in Africa has direct consequences for the security of European countries. The idea of ??a “Fortress Europe” to which the European countries might retreat while remaining indifferent to the violence impacting the neighbouring countries is completely illusory. From this perspective, then, the issue of European defence is not a matter for long-term theoretical political debate; it is a matter of practical inquiry, and one that is quite likely to have a concrete impact.

European countries face significant challenges. The hardships they have overcome in the past have given them the strength to defend our freedom, our values ?and our way of life. Your rapporteurs are convinced that the political will exists to take action both together and with our allies, but in order to do so, we must listen to what our European partners are saying:

“Your own eyes might convince you of the truth,

If but for one moment you could look at me.” 3 ( * )

PART ONE - THE EUROPEAN UNION AS THE SECOND PILLAR OF EUROPEAN DEFENCE: A HISTORIC TURNING POINT TO ENSURE THE SECURITY OF EUROPEAN CITIZENS

The work done by your rapporteurs follow on from your Committee's previous information report on the same subject, entitled “ Pour en finir avec `l'Europe de la défense' - Vers une défense européenne ”, dated 3 July 2013. 4 ( * ) This report denounced the notion of a “Europe of Defence” as a conceptual dead-end that must urgently discarded by building a real “ European defence, ” which it deemed an “ imperious necessity .”

Despite undeniable progress made towards a European defence in recent years, this observation remains a topical one.

I. EUROPEAN COUNTRIES PROVIDING FOR THEIR OWN DEFENCE: A NECESSARY AMBITION

A. A REALITY: THE UNITED STATES STILL PLAYS A PREPONDERANT ROLE IN THE DEFENCE OF THE EUROPEAN CONTINENT

If “European defence” is understood to refer to all the military resources able to be implemented jointly or in a coordinated manner by the countries of the continent, whether within the framework of the European Union or outside it, then it is clear that this European defence plays only a secondary role in the collective defence of Europe today.

1. The slow gestation of European defence poses no challenge to the preponderant role of the Americans

The history of European defence began with a resounding failure: that of the European Defence Community (EDC), rejected by France on 30 August 1954. It marked the failure of the idea of a “European army”: the treaty signed on 27 May 1952 5 ( * ) was intended to establish “a European defence community, supranational in character, consisting of common institutions, common armed forces and a common budget” (Article 1). This European army, placed under the command of NATO, was to provide a way to permit the rearmament of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG).

The idea of ??a European army has never recovered from this initial failure and seems unlikely to do so any time in the near future.

a) The birth of European defence...

After the Second World War and throughout the Cold War, in the face of the Soviet threat, Western Europe placed itself under the protection of the United States. The interests of these two entities (Western Europe and the United States) were very close at the time, even identical, and in the aftermath of the war, their respective resources were completely out of proportion.

The establishment of the Western European Union (WEU) by the Paris Accords (1954), in the wake of the Western Union established by the Brussels Treaty (1948) and after the failure of the European Defence Community (EDC), did not bring this into question. Always in the shadow of NATO, in spite of a certain revitalisation in the 1980s, the WEU remained in the background until it began to be rivalled in the pursuit of its objectives by the European Union, which finally prevailed, since the WEU was ultimately dissolved in 2011.

After the Cold War, the question of the collective defence of the territory and population of the European continent retreated to the background with the collapse of the Soviet bloc, in the absence of a clearly identifiable threat.

This strategic breakthrough enabled the (at least provisional) emergence of the components of a new security architecture, as illustrated by:

- The creation of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) : took over in 1994 from the Conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) which had been created by the Final Act of the Helsinki Conference (1975). The end of the Cold War seemed to have opened a new era of cooperation: “ the era of confrontation and division in Europe is over, ” 6 ( * ) was the belief at the time.

- The signing of a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement between the European Union and Russia (1994);

- The establishment of cooperation between NATO and Russia , which resulted in the NATO-Russia Founding Act of 1997 and the creation of the NATO-Russia Council in 2002.

At the same time, however, European countries were made acutely aware of the need to be able to intervene in their immediate environment, and possibly to do so without the Americans.

The wars in Yugoslavia , which killed about 150,000 people in 10 years (1991-2001) on the European Union's doorstep, were quite revealing in regard to Europe's inability to act outside NATO , i.e., without the United States. The agreements that ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1995 were signed at Dayton, in the United States, symbolising the paralysis of the European countries in the face of the biggest conflict waged on the continent since the end of the Second World War. And once again, it was ultimately the intervention of NATO that put an end to the war in Kosovo twenty years ago.

This collective European failure was the shock that led to the emergence of a common security and defence policy for the EU in the 1990s.

It took a major crisis with a considerable cost in human lives to allow some slow progress to be made and that progress is still incomplete, despite other crises that have given rise to phases of acceleration (Crimea, Ukraine).

While it may be legitimate for progress to be made in this way, in response to each successive crisis revealing the changes in the strategic environment, it would nevertheless be desirable to anchor the ambition for an autonomous European defence in a robust long-term process, and not to wait for another major crisis to erupt on the continent in order to achieve tangible results.

In 1992, with the Petersberg Declaration, the countries of the Western European Union (WEU) decided it would be possible to conduct certain military missions with a limited scope, acting in co-operation with NATO or the EU. These so-called “ Petersberg ” missions include the following:

- humanitarian missions or evacuation of nationals;

- peacekeeping missions;

- missions undertaken by combat forces for crisis management, including peace-making operations.

The Maastricht Treaty, which came into force in 1993, introduced the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) as the second pillar of the EU. In particular, the Amsterdam Treaty (1997) assigned to the CFSP the “progressive framing of a common defence policy, which might to lead to a common defence,” with the objective of carrying out Petersberg missions: ”Questions referred to in this Article shall include humanitarian and rescue tasks, peacekeeping tasks and tasks of combat forces in crisis management, including peace-making.” (Article 17 of the Treaty on European Union in force at the time).

So since the 1990s, Europe has sought to organise itself so as to be able to manage crises on its own by acquiring a “ capacity for autonomous action ,” 7 ( * ) also referred to as an “ operational capacity ” (Article 42 TEU). It has thus gradually built up an ambition for “ strategic autonomy. ” 8 ( * )

In spite of the clause stipulating solidarity amongst European countries established under Article 42 paragraph 7 of the Treaty on European Union (see below), this “strategic autonomy” remains a limited concept. Article 42 of the Treaty on European Union, which has replaced and supplemented Article 17, makes clear, indeed, that “the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation [...] for those States which are members of it, remains the foundation of their collective defence and the forum for its implementation.”

In the course of their travels, your rapporteurs noted that in all the countries they visited, 9 ( * ) it was considered obvious and necessary for NATO to be the cornerstone of European collective defence.

b) ...in no way questioned the preponderant role of NATO...

During the Cold War, NATO devoted itself to its core mission: collective defence, on the basis of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty signed in Washington in 1949, which recently had its seventieth anniversary. This clause, which states that an attack against one of the allies is an attack against all of them, has been invoked only once: by the United States, after the attacks of 11 September 2001. At the time when this Treaty was signed in Washington, the signatory member countries wished to ensure that the United States would automatically come to their aid if one of the signatories were ever attacked. But the United States opposed the notion of automatic action, and thus Article 5 was drafted accordingly.

|

Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty “The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all; and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognised by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area. “Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall immediately be reported to the Security Council. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security.” |

The NATO Strategic Concept (2010) reaffirmed the strength of this commitment: “NATO members will always assist each other against attack, in accordance with Article 5 of the Washington Treaty. That commitment remains firm and binding. NATO will deter and defend against any threat of aggression, and against emerging security challenges where they threaten the fundamental security of individual Allies or the Alliance as a whole.”

This collective defence is ensured up to and including at the nuclear level , with a preponderant role assigned to the American deterrent force, and complementary roles to the French and British deterrent forces: “The supreme guarantee of the security of the Allies is provided by the strategic nuclear forces of the Alliance, particularly those of the United States; the independent strategic nuclear forces of the United Kingdom and France, which have a deterrent role of their own, contribute to the overall deterrence and security of the Allies.” 10 ( * )

The activities of the Alliance were diversified after the end of the Cold War (collective defence, crisis management and security cooperation), but are now being refocused on collective defence so as to confront the “arc of instability” at its periphery.

From the outset, there has been an implicit sharing of tasks in relations between the EU and NATO. The 1998 French-British Saint-Malo declaration already emphasised the ability of the European Union to act “ where the Alliance as a whole is not engaged ” via “suitable military means (European capabilities pre-designated within NATO's European pillar or national or multinational European means outside the NATO framework).” 11 ( * ) The role of the EU in the defence domain was therefore conceived from the outset as complementary, or , one might say, even subsidiary to NATO , so as to avoid any unnecessary duplication of efforts.

The “Berlin Plus” arrangements (2003) consolidated this complementarity, permitting the EU to use NATO planning and operational capabilities in operations in which NATO is not engaged as such. It was on the basis of these arrangements that the NATO operation in Macedonia was transferred to the European Union starting in April 2003, as was NATO's operation in Bosnia and Herzegovina at the end of 2004.

The 2016 Warsaw NATO Summit resulted in an enhancement of EU-NATO relations, on a more balanced basis than had been established under the “Berlin Plus” agreements. This summit led to the adoption of a joint EU-NATO declaration, 12 ( * ) followed by the adoption of 74 common measures in 7 areas of cooperation (hybrid threats, operations, cybersecurity, capabilities, research, exercises, assistance to third countries). This development confirmed, however, that the continent's collective defence, or, for that matter, what is known as “high-spectrum” defence, is primarily a matter for NATO:

“Furthermore, although what I'm going to say isn't written in it, this joint declaration has indeed reaffirmed three basic principles: collective defence is mainly the responsibility of NATO; there will be no European army; and there will be no duplication of the command structures established within NATO. These principles were consistently brought up in every meeting held amongst the Defence Ministers, which NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and European High Representative Federica Mogherini were mutually invited to attend. These principles are laid out in the minutes. They form the basis of cooperation between NATO and the European Union.” 13 ( * )

|

EU-NATO relations 2001 marked the beginning of institutionalised relations between NATO and the EU, based on the measures taken in the 1990s to promote greater European responsibility in the defence field (co-operation between NATO and the Western European Union). The NATO-EU Declaration on European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) adopted in 2002 defined the political principles underlying the relationship, and confirmed that the EU would have guaranteed access to NATO planning capabilities for purposes of its own military operations. In 2003, the “Berlin Plus” arrangements established the foundations necessary for the Alliance to support EU-led operations in which NATO as a whole was not engaged. At the 2010 Lisbon Summit, the Allies emphasised their determination to strengthen the NATO-EU strategic partnership. With the 2010 Strategic Concept, the Alliance committed to working more closely with other international organisations to prevent crises, manage conflicts, and stabilise post-conflict situations. In July 2016 in Warsaw, the two organisations prepared a list of areas in which they sought to intensify their cooperation, given the common challenges facing them to the east and south: combating hybrid threats, increasing resilience, defence capacity building, cyber-defence, maritime security, exercises, etc. In December 2016, NATO Foreign Ministers endorsed 42 measures aimed at furthering cooperation between NATO and the EU in those areas. Further areas of cooperation were decided upon in December 2017 as well. NATO and the EU currently have twenty-two members in common. Source: www.nato.int |

This implicit “sharing of tasks” that is inherent to the EU-NATO strategic partnership, even if it is merely a didactic simplification, remains useful today, based on certain standard ideals, especially those of “collective defence” and “crisis management.” The boundary between collective defence, crisis management and security cooperation (the three missions of NATO) has indeed been blurred, along with the distinction between State and non-State threats.

c) ...nor the role of the United States as Europe's defence partner

The United States does not provide “90 per cent” of the NATO budget, as US President Donald Trump has claimed, but “only” 22.1 per cent of the organisation's budget. The other two primary contributors are Germany (14.7%) and France (10.5%).

But above all, the United States reproaches European countries for not progressing quickly enough towards NATO's 2024 targets - military spending increased to 2% of GDP, 20% of which is to be allocated to major equipment - which supposedly makes them “freeloaders” (the President of the United States would even have preferred this effort to be increased to 4%).

The United States, meanwhile, devotes 3.4% of its GDP to defence, i.e., $605 billion, which is equal to two-thirds of the military expenditure of all NATO countries combined , 14 ( * ) and about one-third of the worldwide total for all military budgets. In 2018, defence spending in the United States was increased by an amount (+$44 billion) itself equivalent to Germany's entire defence budget.

Within this gigantic US military budget, spending specifically devoted to the defence of Europe is estimated at $35.8 billion in 2018, 15 ( * ) or 6% of the total... which is almost as much as the entire defence budget of France (€35.9 billion in 2019).

These expenses are divided between:

- Financing the US presence on the European continent ($29.1 billion), i.e., 68,000 personnel from the five branches of the US military, including about 35,000 in Germany, where the United States European command is located (EUCOM Stuttgart). For the record, in the 1960s there were 400,000 US Army personnel in Western Europe, and 200,000 still in the 1980s.

- The American contribution to NATO ($6.7 billion).

Since 2014, as part of assurance measures implemented by NATO, the United States has increased its presence in Europe via a budget programme known as the “European Deterrence Initiative” (EDI), 16 ( * ) which has provided it with funding for Operation “ Atlantic Resolve, ” (OAR) in favour of the countries of Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania).

The funding of the EDI has steadily increased, from $1bn in 2014 to $6.5bn in 2019. This budget is devoted to strengthening the rotating presence of American forces in Europe, military exercises, the improvement of pre-positioned infrastructure and equipment and, lastly, the strengthening of partner countries' capabilities.

Of course, these figures do not cover all the resources that the United States earmarks for the protection of Europe.

Other aspects of the American contribution to the defence of Europe merit mention here as well:

- As noted above, the United States plays a special role in NATO's strategic nuclear capability , while the United Kingdom and France play complementary roles (France has no nuclear weapons assigned to NATO and is not a member of NATO's Nuclear Planning Group). 17 ( * )

Furthermore, “nuclear sharing” arrangements are in place, which provide for US tactical nuclear weapons to be stationed in several European countries. Though this information is not public knowledge, 5 NATO countries are generally considered to be host countries for these nuclear weapons: Germany, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey. The number of weapons stored in these countries is estimated at 140. As a reminder, during the Cold War, when the United Kingdom and Greece were also host countries, the estimated number of these weapons on the continent exceeded 7,000. The weapons currently in place are B61 bombs. They are intended for use by the air forces of the host country with the agreement of the United States and the host country (via the double-key principle).

More precisely:

“On most of the bases, the weapons are stored under the responsibility of US support units. Bomber fighters from the host country are assigned and pilots trained to deploy these free-fall weapons if the decision is made to use them. Germany thus maintains its 33 rd Fighter Bombers Squadron for this mission, equipped with Tornado PA-200 aircraft. The Netherlands and Belgium have dedicated F-16 crews (10 th Tactical Wing for Belgium, 312 th and 313 th Squadrons of the RNAF). In Italy, the Tornado PA-200s of the 6 th Stormo wing have the capacity to carry B61s as well. At Aviano (Italy) and Incirlik (Turkey), it would a priori be American planes that would be responsible for carrying these weapons.” 18 ( * )

This issue of nuclear sharing is fundamental in an analysis of the procurement policies of the air forces of the countries concerned and, for the future, for the scaling of the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) project.

Estimated number of nuclear weapons in Europe (2018)

Source: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies (as per SIPRI).

- At the request of the United States, NATO is gradually deploying a ballistic missile defence system. This is intended as a response to the Iranian threat and has contributed to a deterioration of relations with Russia. The system includes a major American contribution, decided on in 2009: 19 ( * ) a radar system in Turkey, sites in Romania and Poland, and 4 AEGIS anti-missile frigates based in Spain.

- American supremacy is particularly noticeable in certain areas: strategic transport, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (heavy drones in particular), and refuelling.

Finally, a study was conducted that estimated the cost of the investments that NATO countries would have to make on the purely theoretical assumption of a United States exit from the Organisation , in order to be able to respond to two particular conflict scenarios: 20 ( * )

- 1 st scenario: a challenge to the security of European sea lanes : in this case, the capacity deficit generated by the departure of the United States from NATO would force the European countries to invest between $94 billion and $110 billion to provide for their own maritime security;

- A scenario in which Article 5 is triggered in the context of a conflict on the Eastern flank of NATO (occupation by Russia of Lithuania and part of Poland). 21 ( * ) In this case, to be able to deal with the situation, the European NATO members would have to invest between $288 billion and $357 billion to fill the capacity gaps created by an American withdrawal.

These amounts are not unachievable , since if European NATO countries were to meet the 2% of GDP target, they would already be spending an additional $102 billion per year.

This study thus highlights the implications of the debate on strategic autonomy. It suggests that the debate be refocused on the issue of capability gaps rather than on institutional mechanisms.

“As for the strategic autonomy that France seeks,” said many of our interviewees, “ nobody knows what it means. ” Autonomy does not mean strategic independence; it is a relative notion, in itself insignificant without a definition of the degree of autonomy sought, the investments to be used to achieve that autonomy, and the timetable for its attainment - in other words, unless there is a roadmap for strategic autonomy.

Ultimately, many of our European partners share the opinion of Wolfgang Ischinger, President of the Munich Security Conference:

“There have been lots of sound bites about the strategic autonomy of Europe. But I don't think it's the right way to go. Our reliance on US military capabilities is absolutely necessary for the security of Germany and Europe in the short, medium and long term. We are blind, deaf and powerless without our American partner.” 22 ( * )

2. This is a reality that France must take into account, despite its unique situation in Europe

In view of this dependence on the Americans, France appears as an exception within its environment, having been building its defence apparatus since the 1960s with the aim of national independence.

a) The end of the “French exception” in NATO

When it was created, France actively supported NATO so as to definitively involve the United States in the defence of Europe and thus preserve peace. The headquarters of NATO was then set up in France, until General de Gaulle's 7 March 1966 decision to cease France's participation in the Organisation's integrated command structure whilst still remaining within the Alliance.

This unique situation came to an end in 2009, when President Nicolas Sarkozy decided to restore France's participation in the integrated structures with the notable exception of the Nuclear Planning Group .

Thus, “by its return to the NATO Integrated Military Command in 2009 while preserving its special status in the nuclear domain, France fully acknowledged NATO's role in European defence.” 23 ( * )

President François Hollande maintained this approach. In 2012, in a report 24 ( * ) on this subject, Hubert Védrine, former Foreign Affairs Minister, took the position that a new exit was not possible, whatever the benefits of France's return to NATO's integrated command, which he deemed to be mixed:

“France's (re)exit from the integrated military command is not an option. Nobody would understand it in the United States or in Europe, and it would not give France any new leverage - quite the contrary in fact. It would instead ruin any possibility France has for action or influence with any other European partner in any area whatsoever. Furthermore, from 1966 to 2008, that is, in more than 40 years, not a single European country ever expressed support for France's position on independence.”

If a certain French exception still remains in NATO, it has only to do with the status of our deterrent force.

b) Strategic autonomy and nuclear deterrence

Of all the countries of the European Union and the European partners of NATO, France is the only one to pursue an aim of national independence within the framework of defence cooperation, although without ruling out certain interdependencies, as underlined in the Defence and National Security Strategic Review of December 2017.

Even the United Kingdom, also a nuclear power and our most similar partner within Europe, has seen its striking force as being closely linked to that of the United States and the NATO framework since the 1962 Nassau Agreement.

This significant difference in strategic culture is a parameter that must be taken into account in the dialogue on strategic autonomy at the European level.

Semantics is a problem in itself. The term “ deterrence ” is not understood the same way everywhere in Europe: in NATO, for example, this concept refers to a set of measures, in the conventional field as well, that are intended to require any adversary to face risks that will outweigh any potential gain. In German, the word “ Abschreckung ” (deterrence), which is associated with the words “fear” and “fright,” has a very negative connotation. European public opinion is generally not very familiar with the French concept of deterrence, i.e., the idea of ??defensive nuclear weapons, the purpose of which is to inflict damage that would be unacceptable to the enemy, one of the characteristics of which is that they are always ready to be used, so that they will never have to be used. In this sense, nuclear arms are a fundamentally political weapon.

“For France, nuclear arms are not intended to gain an advantage in a conflict. Because of the devastating effects of nuclear weapons, they have no place in any offensive strategy; they are seen only as part of a defensive strategy. Deterrence is also what permits us to preserve our freedom to act and make decisions under all circumstances (...). It is the supreme responsibility of the President of the Republic to constantly assess the character of our vital interests and of any attacks to which they may be subject.” 25 ( * )

In 1992, however, President François Mitterrand did raise the question of the relationship between French deterrence and European defence, asking, in the aftermath of the Maastricht Treaty: “Would it be possible to imagine a European doctrine (of deterrence)? That is going to be one of the big questions in terms of building a common European defence.”

In 1995, at the Chequers Summit , France and the United Kingdom jointly affirmed that any situation that might arise threatening the vital interests of either one of their two nations would be considered a threat to the vital interests of the other as well. 26 ( * )

The issue was brought up time and again in the following years by all the Presidents of the French Republic:

- Jacques Chirac: “The development of the European Security and Defence Policy, the growing integration of the interests of the countries of the European Union, and the solidarity that now exists between them, make the French nuclear deterrent, by its mere presence, an essential element in ensuring the security of the European continent.” (Ile Longue speech, 19 January 2006);

- Nicolas Sarkozy: “It is a fact that by their mere presence, French nuclear weapons are a key part of Europe's security. Any aggressor that might consider challenging Europe would have to take them into consideration.” (Cherbourg speech, 21 March 2008);

- And François Hollande as well: “The definition of our vital interests cannot be limited simply to the national level, because France does not see its defence strategy as existing in a vacuum, even when it comes to nuclear arms. We have expressed this position many times to the United Kingdom, with which we have established an unparalleled degree of cooperation. We are participating in the European project, and have built a community of destiny with our partners; the existence of a French nuclear deterrent makes a strong and essential contribution to Europe. Furthermore, France stands in solidarity with its European partners, a solidarity that is both in fact and in feeling. Who then could ever dream that any attack seeking to threaten the survival of Europe would have no consequences? That's why our deterrent force goes hand in hand with the constant strengthening of the Europe of Defence. But our deterrent force ultimately belongs to us alone - it is we who make the decisions about it, and it is we who must assess the state of our own vital interests.” (speech given at Istres, 19 February, 2015).

Your rapporteurs asked about the European aspect of the French deterrent force in the European countries they visited, for example by framing the question as follows: By advocating strategic autonomy for Europe, is France seeking to place all its partners under its “nuclear umbrella”? While pointing out the abovementioned statements, tending to give a European dimension to what are identified as the “vital interests” of France, your rapporteurs also reminded the interviewees of the fundamental principles underlying the French deterrent force, a component of our national sovereignty, the deployment of which is exclusively its own responsibility, and must remain the sole prerogative of the President of the French Republic.

Although rarely debated in France, the idea of ??the Europeanisation of the French deterrent force is nevertheless gaining momentum around Europe , though there is no consensus on the matter. The proponents of this course of action suggest that it might be possible to permit “double key” nuclear sharing arrangements with France on the model of those now in place with the United States, or to institute a contribution from Germany, or from a group of several EU countries, to help provide funding for the French deterrent force. 27 ( * ) In 2017, the services of the Bundestag determined that strictly from a legal perspective there would be no obstacles to the potential establishment of such a financial contribution.

Wolfgang Ischinger, chairman of the Munich Security Conference, believes for his part that sharing the financial burden of deterrence would not be incompatible with maintaining the current pattern where deployment is exclusively under the authority of the President of the French Republic:

“In the medium term, the question of a Europeanisation of French nuclear potential is indeed a very good idea. It is a matter of knowing if and how France might be willing to strategically place its nuclear capacity at the service of the European Union as a whole. Concretely speaking: the options for an engagement of nuclear force by France would need to cover not only its own territory, but also the territory of its partners in the European Union. In return, we would need to define what the European partners could bring to the table for this purpose, so as to achieve a fair distribution of contributions. However: any possible use of nuclear weapons could not ultimately be decided by an EU committee. This decision would need to remain up to the French President. And we would have to accept that responsibility! ” 28 ( * )

It is nevertheless quite premature to discuss any possible sharing by France of its nuclear deterrent force. The voices that have been raised in this regard are alone and are not representative of any majority of political forces or public opinion amongst our European partners.

It must be borne in mind, however, that for a number of observers, particularly in countries that rely on the supreme guarantee of US nuclear forces, such a debate might be considered to follow logically as a consequence of France's active engagement in favour of the strategic autonomy of the EU.

B. “SHARING THE BURDEN”: A NECESSITY FOR EUROPEANS

1. The historical role of the United States in Europe since the Second World War

Since 1945, Europe has been in a situation that has never occurred since the fall of the Roman Empire: it has largely lost its responsibility for defending itself. Several countries in Eastern Europe underwent Soviet domination from 1945 to the 1980s, which for half a century deprived them of the possibility of determining their own defence policy. In Western Europe, in the context of the Cold War, the European countries by and large placed themselves under US protection, in the framework of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) created by the Washington Treaty of 4 April 1949.

Only two countries have chosen to maintain an autonomous capacity to defend their vital interests by rapidly acquiring nuclear arms: the United Kingdom (which has had nuclear weapons since 1952) and France (which has had them since 1960).

Even today, the United States accounts for about two-thirds of NATO efforts. The situation now, however, is that faced with the growing challenge of China's hyper-power status, the United States has made clear to its European allies that it no longer intends to play such a substantial role in the defence of Europe. That is what the United States means by its regularly repeated demand for “burden-sharing.” By the time of the 2006 Riga Summit, the allies had agreed to raise their national spending to a minimum of 2% of GDP. It was in this context, that this prospect was confirmed at the 2014 NATO Summit held at Newport, by a specific commitment that the allies would make that figure the goal to be reached in 10 years. 29 ( * ) A second goal was that at least 20% of these defence budgets would be allocated to equipment purchases.

In fact, the end of the Cold War led the European States to believe that they would be able to “collect the dividends of peace” by continuously reducing their defence efforts.

The significant element of this new context is that two developments not directly related to one another have met and converged:

- On the one hand, the United States has found itself facing challenges on a global level of a kind not seen since the Second World War, and has felt the burden of its commitment to European defence more acutely;

- On the other hand, the European States have become increasingly aware of the threats they face, especially in the wake of Russia's annexation of Crimea. This was a symbolic shock, because it dramatically manifested Russia's will and ability to challenge internationally recognised borders, including those that it had itself recognised until then.

Source: NATO

The graph above shows the increase in the share of defence spending in GDP for most European countries between 2014 and 2019. Expenditures have increased for the fourth year in a row. However, for the time being, the majority of European NATO members still fall short of the 2% of GDP criterion. 30 ( * ) This is particularly the case in Germany, at 1.36%; Italy, at 1.22% and Spain, which is at 0.92% of GDP.

Here, American and European perspectives diverge. It is quite clear that for the United States there is no common measure between these two challenges. For the United States, China is a universal competitor, contesting American supremacy in all domains: first of all in the economic domain, then in the financial domain, and in the cultural, diplomatic and strategic domains as well. In this competition, the military dimension does not dominate, although it is present.

Russia has the opposite profile: it is a country with a weak economy, and a GDP between those of Spain and Italy - even though it is the largest country in the world and endowed with considerable natural resources. In addition to this, the Russian population is undergoing a net decline. Though Russia's interventionist and sometimes provocative policies pose a clear and immediate threat to European countries, and are of course more urgent for those closest to it, it does not pose a threat to US pre-eminence worldwide. These are the issues at stake in the organisation of the system for arms control in Europe, a matter that is of key importance for Europeans. In this light, the scheduled expiration of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty next August is extremely concerning. Significantly, the issue is the subject of very broad consensus in Europe.

This, then, is the deep root of the awakening of the European spirit of defence: our fundamental security and defence interests have diverged from those of the United States. But this divergence, of course, does not mean opposition.

Extremely strong ties unite the countries of Europe to the United States. These ties are multiple, and range across all the economic and social fields, but in general they may be considered as being of two fundamental types:

- First there are blood ties, forged in common military engagements against common enemies. While these ties are particularly old in the case of France, it can be said that they include all European nations, in respect of the liberation of Western Europe in 1944-1945. As we have lately been commemorating the 75 th anniversary of the Normandy landings, your rapporteurs here wish to take a moment to salute the memory of the thousands of American soldiers who gave their lives during the campaign in France. Their sacrifice cannot and will not ever be forgotten, and has forged an eternal bond between our two peoples.

- Then there are ties of a political nature. The United States is a democratic regime, based, in the same philosophical and ideological tradition as the European countries, on the belief that every individual has inalienable rights, and that the rights and duties of all members of society are defined and protected by the rule of law. This is an abiding, fundamental difference between the United States and other powers like China or Russia.

The use of the term “burden-sharing” in regard to European defence would thus seem appropriate. In substance, then, it is difficult to see what could lastingly justify Europe's continued under-sizing of its defence efforts.

2. Stabilisation does not yet mean rearmament

The analysis of quantified comparisons made by the Swedish Institute SIPRI helps put European defence efforts into perspective. A medium-term analysis of these comparisons (over a decade) shows some surprising results. Looking at the period between 2008 and 2017, SIPRI has identified four groups of countries: 31 ( * )

- Those whose defence budgets have substantially increased, by at least 30%: China, Turkey, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia and Australia;

- Those whose defence budgets have increased by between 10% and 30%: South Korea, Brazil and Canada;

- Those whose budgets have increased by less than 10%: Germany, France and Japan;

- And those whose defence budgets have fallen: Italy, the United Kingdom and, above all, the United States.

Particular attention should be given to the United States and the main European countries. Over this period, the defence budget of the United States decreased by 14%, and was down 22% from its peak in 2010, when increased efforts were being made in Afghanistan and Iraq. This relative decline cannot, however, conceal the massive size of the US military budget, which in 2017 came to $610 billion, 2.7 times that of China, the second-biggest military spender.

In that same year, 2017, all the European countries combined (including Russia, in keeping with SIPRI classifications) spent $342 billion, i.e., 56% of the US effort. Unsurprisingly, the largest defence budgets in the European Union correspond to the largest countries, in the following order: France (6 th in the world), United Kingdom (7 th ), Germany (9 th ) and Italy (12 th ).

As the SIPRI report points out, the relative weight of these four major European countries in global military spending has dropped by one-third over the last ten years. In 2008 they accounted for 15% of military spending in 2008, but for just over 10% in 2017.

The shift in the world's military centre of gravity is very telling. In 2008, these four European countries together spent 2.6 times more than China. Ten years later, their expenses are a quarter less than China's (78%). 32 ( * )

It is also interesting to compare the combined spending of these four countries with Russia's spending. According to SIPRI, Russia spent $66.3 billion in 2017, which is 15% more than France. If we add to this the expenditures of the four largest EU countries, Russia's military expenditure accounts for a little over one-third of this combined amount (37%). On several occasions during their interviews, your rapporteurs raised the question of this paradox with regard to Russia, a country that is perceived as a great military power but whose spending is lower than that of Saudi Arabia, and falls within the same order of magnitude as the main European armed forces. The paradox was explained in various ways:

- One suggestion was that the numbers we know about only account for a portion of actual military spending. This argument may be valid. Still, it is hard to imagine the difference in values for the official figures going from one to two orders of magnitude. And even if the Russian military effort were in fact twice the estimate made by SIPRI, the figure would remain significantly lower than the figure for the European countries;

- A second and likely more relevant explanation is that the Russian effort is proportionately concentrated in a few high-end domains in which it has traditionally excelled: aeronautics (fighter jets and missiles), 33 ( * ) space, submarines, and of course its nuclear power, in which it remains a force to be reckoned with. Doubtless to this must be added its more recent development of cyberweaponry, which can be considered as a modern version of mathematics, another field in which Russia has long excelled;

- Another point to consider is that members of the armed forces in Russia are in general paid less than members of the armed forces in Europe, which accounts for a significant portion of defence efforts;

- And lastly, compared to other European countries, Russia enjoys a considerable but not quantifiable advantage: unity of command. The Russian army has one commanding authority, one hierarchy, one language, and one equipment range. Obviously, on the operational level, these are very important assets.

3. Europe's rise as a military power has only just begun

The primary mission of States has always been to defend their territory and the people who live there. From a historical perspective, the weakness of the defence effort of the European nations must be seen as a temporary interlude that eventually had to come to an end. Looking back on the interviews and visits they conducted around Europe, your rapporteurs are convinced that for the most part, our European partners are aware of this reality.

It is therefore essential that we see the debate between Atlanticists and defenders of a Europe entirely independent of the United States - and we should emphasise that there are very few of the latter in Europe - for what it is, i.e., as a false debate, and an artificial one at that, more to do with politicians and their personal aims than with real policy issues.

The reality, in fact, is perfectly logical:

- European defence today is dependent upon on the United States;

- The United States is calling for an end to this situation, first of all because they want to be able to concentrate their efforts on their rivalry with China, and secondly because they feel that European countries have benefited from the American presence to obtain substantial savings on their defence budgets;

- The United States and therefore NATO furthermore consider that some of the security challenges Europe is facing are not their responsibility: such would be the case, for example, for immigration crises, or for stabilisation and peacekeeping operations in the European neighbourhood. In the words of one of your rapporteurs' interviewees, “the Mediterranean, Africa and the Middle East will pose major challenges to the security of Europe in the coming decades. But NATO isn't interested, because that's not the purpose it was designed for”;

- European countries are therefore obliged to increase their defence effort;

- But this “burden-sharing” can only be achieved in a gradual and concerted manner amongst the European countries and the United States, so as not to weaken the defence of the European territory.

Thus, far from being in competition with one another, NATO and European efforts in fact converge to ensure the security and defence of Europe. A kind of implicit sharing of roles is in place, which could benefit from some clarification, so as to dispel any fears amongst our partners:

o NATO is responsible for the defence of European territory and the management of high-end threats;

o The European Union and European States acting in intergovernmental frameworks are responsible for ensuring “forward defence,” i.e., interventions outside Europe and security missions, such as migration control or anti-trafficking efforts. It is relevant to point out that the notion that the defence of Europe must include the ability to reach beyond the confines of Europe is not always clearly understood by some of our European partners. Yet one needs only look at the resolute actions taken in the Middle East by Russia to see how the eastern and southern fronts, far from being disconnected, are in fact often linked. The same is true in Africa, which has become a field for fierce competition amongst world powers.

Lastly, the complementary relationship between NATO and the EU is also due to the differences in their members. The most notable of these differences is that NATO includes the participation of Turkey, which for example blocks Cyprus, a member country of the European Union, from becoming a member of the Organisation.

Your rapporteurs propose:

- That the application of the military planning law (LPM) enacted by the Parliament should be safeguarded, particularly in regard to its provision for a rise in defence credits to 2% in 2025, and that the first step towards French participation in European defence should be to confirm our country's commitment to defence;

- That the unproductive notion of an opposition between NATO and the European Union should be abandoned, because they are in fact complementary and not in competition.

II. THE EU AS A MAJOR STAKEHOLDER IN EUROPEAN DEFENCE: THE NEXT STEP NOW BEING TAKEN

The Treaty of Lisbon, which came into force on 1 December 2009, created the conditions for the strengthening of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP); this paved the way for involvement in the defence domain by the European Commission through the creation of the European Defence Fund.

If sufficiently confirmed by the new EU institutions, these developments will mark a historic turning point.

A. THE EMERGENCE OF THE EU AS A MAJOR STAKEHOLDER IN EUROPEAN DEFENCE

1. Strengthening the common foreign and security policy

The texts have reinforced the Common Foreign and Security Policy, which entered into force in 1993 under the Maastricht Treaty (once known as the “second pillar”), giving it a wider scope and additional tools. On the ground, however, the EU's foreign policy is struggling to take shape and project the image of “Europe as a world power.”

a) Institutional reinforcement of the CFSP/CSDP

The Lisbon Treaty manifestly strengthened the CFSP by creating the post of High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Vice-President of the Commission (HR/VP), and the European External Action Service.

Article 42 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) defines the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) as a component of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). It stipulates that the EU may make use of civilian and military assets outside the Union “for peace-keeping, conflict prevention and strengthening international security in accordance with the principles of the United Nations Charter.” The capacities necessary for the accomplishment of these missions are to be provided by the Member States.

Decisions in regard to CFSP/CSDP are to be taken unanimously by the Council, except in specific cases (Article 31 TEU). The adoption of legislative acts (regulations, directives) is excluded.

The Treaty of Lisbon also supplemented the scope of the CSDP resulting from the Petersberg missions, to include joint actions in the disarmament field, military advisory and assistance missions, conflict prevention missions and post-conflict stabilisation operations. All these missions can contribute to the fight against terrorism, as well as by providing support to third countries to fight terrorism on their territory.

In June 2016, the HR/VP presented to the European Council a European Union Global Strategy on Foreign and Security Policy (EUGS). This global strategy identifies five priorities for the Union's foreign policy: the security of the Union, the resilience of the States and societies in the EU's eastern and southern neighbourhoods, the development of an integrated approach to conflict, regional cooperative arrangements, and global governance.

The European Council of 28 June 2016 indicated that it “welcomed with interest” this Global Strategy, which has multiple ramifications (see inset) including the ambition of strategic autonomy for the European Union. The European Council of 15 December 2016 then launched several initiatives to strengthen EU action in the defence domain.

The last report on Global Strategy was delivered at the meeting of the Council on Foreign Affairs held 17 June 2019, at which HR/VP Federica Mogherini presented the third progress report on the EUGS and a report on her activities as HR/VP. In the implementation of this Strategy, France is particularly dedicated to the consolidation of strategic autonomy, understood as greater independence in terms of Union decision-making, assessment, and action, which are necessary in order to enable the European nations to participate in ensuring their own security, contribute to greater burden-sharing, and cooperate on an equal footing with our partners.

|

2016-2018: progress of the CSDP In November 2016, the Council reviewed an “Implementation Plan on Security and Defence”, which was intended to operationalise the vision set out in the EUGS in regard to defence and security issues. To meet the new level of ambition, the plan included 13 proposals, including a Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) focusing on expenditures; a strengthening of the Union's rapid reaction force, in particular by recourse to European Union Battlegroups; and a new, unified Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) for Member States seeking to increase their engagement in security and defence matters. On 30 November 2016, the HR/VP presented the Member States with a European Defence Action Plan (EDAP), containing key proposals for a European Defence Fund dedicated to defence research and the establishment of defence capabilities. The Council also adopted conclusions approving a plan intended to implement decisions on EU-NATO cooperation adopted in Warsaw (42 proposals). These three combined plans, which some have referred to as the “winter package on defence” were a major step forward in the implementation of the Lisbon Treaty in the security and defence domain. In March 2017, the European Council took stock of the progress made, highlighting the creation of the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC), a new structure designed to improve the Union's ability to respond more quickly, more effectively, and more flexibly in the planning and execution of non-executive military missions. It also noted progress made in other domains. For example, in November 2018, it highlighted the substantial progress made over the last two years in areas such as the Civilian CSDP Compact, the development of the MPCC, the implementation of PESCO, CARD, and the European Defence Fund, strengthening cooperation between the Union and NATO, promotion of the proposal for a European Peace Facility, and military mobility. In December 2018, EU leaders also commended the progress made in the areas of ??security and defence, including the implementation of PESCO, military mobility, and the Civilian CSDP Compact. Source: http://www.europarl.europa.eu |

The efficiency and speed of decision-making in the CFSP/CSDP domain is undermined by an institutional barrier: the unanimity rule, which is the focus of regular debate. This rule may be overridden without requiring an amendment to the treaty if the European Council unanimously decides to adopt a resolution providing for the Council to act by qualified majority (Article 31 (3) TEU, known as the “bridging clause”: “The European Council may unanimously adopt a decision stipulating that the Council shall act by a qualified majority...”)

This clause has never been invoked. It is, however, not applicable to decisions with military or defence implications.

In 2017, the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, advocated reducing the systematic use of unanimity on foreign policy issues. In September 2018, the Commission identified three specific areas in which such a change might be made, when it is necessary to:

- respond collectively to attacks on human rights;

- apply effective sanctions;

- or launch and manage civilian security and defence missions.